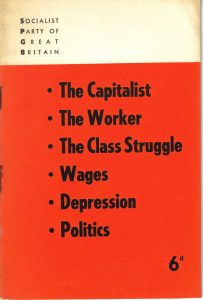

PDF version* The Capitalist * The Worker * The Class Struggle * Wages * Depression * Politics

Wage and salary earners have endless problems to worry about – problems of wages and prices, rents and mortgages, and how to provide against sickness, unemployment and old age. The usual attitude is to regard these problems as ones that can be dealt with by the trade unions or by new Acts of Parliament, and at each General Election the Labour, Liberal and Tory Parties tell the voters about the new laws they will introduce if they become the Government.

The Socialist Party of Great Britain views things differently. We say that the social system itself needs to be changed fundamentally, that is, the class relationships and the way production and distribution are carried on. This goes much deeper than a mere change of government but it can never be brought about unless there is widespread understanding of what needs to be done.

The first step towards understanding is to realise what are the relationships between the owners of industry and the workers they employ, how wages and profits are determined, what causes crises and so on. This pamphlet is intended as an aid to understanding these problems.

A word of explanation is necessary about the material in this pamphlet. It was written by a Canadian worker, a member of our Companion Party, the Socialist Party of Canada, and then published in America by the World Socialist Party of the U.S.A. For this reason it contains references to political and economic events on the American continent which will, however, present little difficulty to the reader in this country and are a useful reminder that the workers’ problems are essentially the same in all countries, and that the solution is the same – Socialism!

Executive Committee

Socialist Party of Great Britain

April 1962

Contents

The Capitalist

The Capitalist is a frequently misunderstood person. He is often portrayed in something less than glowing terms. Not that his clothing is shoddy. Usually it is shown to be carefully tailored and made of costly materials. But he is offered to us as a smirking, pear-shaped specimen, lips folded over a fat cigar, whose weight is mainly encompassed by his belt. Sometimes he appears as a banker, a big bad banker, who has corralled all the money and won’t let the rest of us have any except at impossible rates of interest. Sometimes he turns up as a munition maker who plots to keep the world at war so that he may sell his guns and tanks and other wares and keep the profits flowing in. Then, again, he may be a landlord whose girth is gained from high rents on slum dwellings inhabited by poor people.

He may be found in any of these categories, or he may be found in any of a number of other categories equally distasteful. Indignant people are the ones who portray him in these terms. People who believe that more of the good things of life could come to those in need if more money or cheaper money were made available, or that wars could be reduced in number or intensity if profits were removed from the sale of arms, or that better or cheaper housing would be possible if curbs were placed on his bad habits. Indignant people, rebellious people, people who see wrongs in society that must be righted, and who see in the capitalist the source of so many of these wrongs.

Then there are other people who portray the capitalist differently. They see in him a public benefactor, a philanthropist, a captain of industry, a financial genius, an all-round fine fellow. Press reporters and politicians often tell of his benefactions and sterling qualities. Preachers and elderly ladies dote on his philanthropies. Educators discourse on his industrial and financial greatness.

In the eyes of these good people he brings grace, goodness and distinction to a society which, with all its faults, already scintillates with fine features. The way people look upon society has much to do with the way they look upon the capitalist. Those who see evils about them tend to place these evils at his door. Those who observe instead blessings in modern life tend to credit him with these blessings. He is truly the object of much attention.

And most of it is undeserved. It is unquestionably true that he picks up a dollar here and there through colourful banking operations, the sale of guns, the renting of rat traps and other indiscreet activities. And it is equally true that his industries provide jobs for people, that he contributes generously to churches and charities, that he gives his support to all kinds of groups engaged in social uplifting and public improvement, activities widely conceded to be of worth. But he is really not much different from the rest of us. There may not be patches on his britches or holes in his socks, or callouses where ours are. He may have better clothing, a finer home, a more attractive bank balance. But he could walk along the road with any of us – and who could determine which one owned the alarm clock?

The thing that makes him a capitalist is not the thing that makes him good or bad in people’s eyes. Most people don’t even give a thought to the thing that makes him a capitalist. They content themselves with some particular feature of his activities and judge him accordingly.

He is a wicked banker, a blood-stained munitions maker, a thieving landlord. Or else he is the embodiment of many virtues.

The most important thing to note about the capitalist is that he is a member of an economic category. He belongs to a class in society – the capitalist class. As such he shares with his fellow capitalists in the ownership of the mills, mines, factories, in fact, all the means that exist in society for producing and distributing the food, clothing, shelter and other things needed for the preservation and enjoyment of human life. He and his kind own all these things: the rest of society don’t own them. It is this fact of ownership that determines in the long run what he thinks and does and how he lives, and how the rest of us live.

Consider the position of the capitalist and his factory. Into the factory go raw materials and workers and out of it come products that are sold in the market places to bring him a profit. The profit does not originate in the market places. People who manipulate wealth in market places do not in that way create profit; they simply shuffle it around in such a way that some capitalists benefit at the expense of others. The profit is created by the workers in the factory. It exists in that portion of the wealth which the workers produce in excess of their own wages.

Not all of it is profit but there is no profit to be found elsewhere. To increase the amount of his profit the capitalist must improve the methods of production, or he must induce the workers to work longer hours or at greater speed, or to accept lower wages. And unless he is prepared to sweat in the factory beside the workers, a thought that is usually repellent to him, there is not much else he can personally do about the profit except spend it. This he does with all the assurance of one who is entitled to it.

The capitalist is a parasite. He lives without working. He lives on the results of other men’s toil and he is able to do this because he owns the means of production and distribution, a condition that is neither necessary nor desirable but is allowed to continue because people have not yet seen in it the source of most of the harm in modem society. For even those who rise indignantly to condemn the capitalists, in most cases condemn only the ‘wicked’ ones.

To replace wicked capitalists with worthy ones will not end the exploitation of labour. The workers will continue to live in need, in insecurity, in fear of the future, no matter what may be the quality of those who occupy the high places. What is wrong in society is not the wickedness of the capitalists but the wickedness of the capitalist system; and until this system is replaced by one in which there are no capitalists, society can have no hope for a better life. It is not proposed here to imprison or exterminate the capitalist; it is proposed simply to put him in overalls and make him a useful member of the community.

The Worker

On Mediterranean shores, on the sands of Waikiki, on Caribbean waters, these are among the places where the worker is to be found. But not in great number and not stretched out on his back. He will be found in these places in just those numbers that are required to wash, clothe, feed and minister in other ways to the wants and comforts of people who have neither the need nor the urge to look after themselves.

There are places where the worker can be found in far greater numbers: the swamps of Florida, the forests of British Columbia, the auto plants of Michigan, the mining camps of Ontario; places that he is far more accustomed to, where the produce of nature is moulded into things useful to man; far places, near places, places of dirt and smoke, sweat and work.

The worker is a handy sort of person to have around. Without him the Mediterranean shores would lose most of their splendour, the waves would wash over Waikiki unsung by travel agencies, the waters of the Caribbean would abound in ocean life undisturbed by intrepid sportsmen. Without him there would be no smoke over Pittsburgh, no satellites over Moscow, no grandeur in Rome, no pomp in London; no magnificence in Washington, no bull in Ottawa; no joy in the hearts of those who live without working.

To ensure that he creates an abundance of the finer things of life for other people and a sufficiency of other things to care for his own needs, in the way of food, clothing and shelter, plus a bit extra for tobacco and the raising of a family to take his place in production when he grows old, and also to ensure that this state of affairs be protected to infinity, is the fondest aim of those in whose care rests the destiny of society .That is the blessed eternity that the owners of the world and their spokesmen dream and yearn and sigh for. What finer world could be envisaged than one in which the workers work happily on simple fare and the nonworkers live happily on the rest?

Somehow this doesn’t sound just right, does it? Somehow it seems that somebody is getting away with something; that there should be a better set-up than one in which the workers wind up with rations, while people who do nothing useful live on the fat of the land. Yet that’s how it is.

There is a lot said in high places about talking turkey to the Russians and hanging one on the nose of some other foreigner. There are grandiose plans in governing circles for intercontinental guided missiles and improved types of atomic bombs.

There is much said about foreign trade, tariffs, agreements and embargoes. The world we live in treats the wealth of the owning class with the greatest reverence. It has to be guarded by every means, shifted here and shifted there, moved within the terms of international understanding, cared for and catered to in every way that will benefit the owners. And these antics are all assumed to be in the interest of the whole community, the theory being that what is good for General Bullmoose is good for everybody. But after everything has been done according to plan, it still works out that the worker finds himself by the palm trees, the rolling waves, the silvery sands, for no better reason than to work. Either that or he is trespassing.

It doesn’t have to be like that. But if someone thinks that maybe the other fellow will do something about it, he had better move back to the beginning and start thinking some more.

The other fellow has too many things to do. He has a world in his lap, placed there by the worker. How can he enjoy to the full the bounteous produce of labour and at the same time concern himself about its grubby producer? Besides, what can be wrong with a world that is so full of wonderful things and places – and so much time in which to enjoy them:

Thoughts like these are hard to counter. There is logic in the other fellow’s position – logic for him. But it could be different for the worker. This kind of logic doesn’t help to build up his supply of caviar or contribute to the upkeep of his coach and four. He needs more. And when he has gotten down to some serious thought and study and found out what really goes in on society, there is no doubt whatever about the outcome: he will know what needs to be done and he will know who has to do it.

He will know that the reason he and his family and his kind receive so little, while the other people mentioned receive so much, is that he and his kind are members of the working class, having no share in the ownership of the means of production and distribution and forced in order to live to work for these other people, the members of the capitalist class. He will know that the workers are forced to do this because the capitalists own the means of production and distribution and will allow their operation only on condition that it brings them a profit.

He will know too that this profit comes from the amount of wealth produced by the workers in excess of their own essential needs, and that the capitalists’ constant pressure is to increase this excess and so their profit, even to the extent of lowering the subsistence level of the workers. Knowing this he will also know that the only way for the workers to rid themselves of the shackles of subservience and want is to transform the means of production and distribution from capitalist property to common property, introducing at last a condition in which human needs will be satisfied, unaffected by the restraints, dictates and diversions of an owning class.

And since the class ownership of the means of life is protected for the capitalists by their control over the government, the worker will know too that he and his fellows must become organized in a political party designed to bring about the necessary transformation. Then he will join the Socialist Party.

The Class Struggle

The Class Struggle! When this term crops up one almost feels the vibrations as the neighbourhood shudders and the heads plunge into the sand. “There ain’t no such animal!” reports a muffled voice from the gritty depths. “Figment of a distorted imagination!” proclaims an indignant variant. How often have we heard these thoughtful pronouncements levelled at those who think there are lions among the lambs on this gentle planet!

Yet there is a class struggle in society, right here and right now. What’s more, the world has been witnessing the spectacle of classes in conflict for a long, long time.

It first came about in remote times, back some 6000 or more years ago. Man had expanded and developed his methods of obtaining the requirements of life to the point where it was possible for him to produce more than his own needs, a condition that led to the division of society into classes. These classes were made up on the one hand of those whose function it was to produce wealth and perform useful services, and on the other hand of those, at first assigned functions considered to be useful or desirable, who finally developed into a class with no function other than to surround themselves with wealth and privileges and means for protecting these conditions.

Men at this time stood in the relation to one another of master and slave and the earliest societies in which slavery prevailed were known as Chattel Slave societies. The Pyramids of Egypt, the Parthenon of Athens, The Colosseum of Rome, all were built during a period when slave society had reached a high degree of development, the slave states of Egypt, Greece and Rome being among the greatest in the ancient world.

Where there are classes there is servitude, and where there is servitude there is conflict. No account of early slave society is complete without reference to the struggles of the slaves to gain their freedom, struggles that sometimes reached massive proportions. Amongst the most noted of these struggles were those led by the slave, Spartacus, who rallied 100,000 of his followers in a bid for freedom against the Romans, to be finally killed in battle, his followers captured, 6000 of whom were crucified.

The slave states of antiquity were succeeded by feudalism, which spread through Europe following the decline of the Roman Empire. Feudalism was also a class society, but the basic division was between serf and lord rather than between slave and slave owner as formerly.

The serf was bound to the land, part of which he cultivated for himself and family and part for the lord. The shackles of this form of servitude were no less binding than were those of the chattel slaves and no less productive of rebellion amongst the victims, as shown by the peasant revolt in England under Wat Tyler in 1381 and the peasant war in Germany under Thomas Muenzer in 1525. These and other outbreaks in various parts of Europe during this period were crushed, often with great brutality.

We no longer live under Chattel Slavery or Feudalism, but mankind has not yet rid itself of classes. The society of today is a capitalist society and the classes that face one another are the capitalist class and the working class. The form of bondage is different from the forms that prevailed formerly, but it is still bondage.

The wealth producers of today are not bound to a lord or master as were the serfs and slaves. They may refuse their services to this or that capitalist. But they cannot escape from the capitalist class. They must deliver their abilities to some member or members of that class. In no other way do they have access to the things needed to preserve life.

And in spite of the often repeated claim in various circles that the classes of today have mutual and harmonious interests, the facts show a struggle between these classes as grim as any that preceded it. From the beginning of the existing form of society down to the present day there has been a never-ending conflict between the capitalists and the workers: on the part of the capitalists to squeeze every possible ounce of energy from the workers at the lowest possible cost; on the part of the workers to check these efforts and to try in turn to gain bearable living and working conditions for themselves. The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 and the British General Strike of 1926 are among the more noted evidences of this conflict in recent decades, although there have been far more bitter manifestations in many parts of the world.

The class struggle has a very real existence in modern society. By means of the class struggle the capitalists rid themselves of the restraints of Feudalism and became the dominant class in society. By the same means will the workers rid themselves of the restraints of capitalism – when they have come to know that efforts directed solely to easing the hardships of their own subservience are not sufficient and that they must, in their own interest and in the interest of all humanity, do away with all forms of human bondage, by doing away with the thing that divides humans into classes – the class ownership of the means of life – and transforming the means of life (the mills, mines, factories and so on) into the common property of all, operated for no other purpose than to bring security and happiness to the human race.

Contents

Wages

Working people live on wages which are obtained in their places of employment. Some workers own government bonds or company shares and derive income from these and from other sources. But all sources other than wages form a very small part of the average workers’ income. Mainly the workers live on wages and any changes that occur in the amount of wages have a definite bearing on their conditions of life.

The wages which they receive represent a portion of the wealth they produce. This portion takes the form of money and is given to them by the owners of the places where they work in return for the use by the owners of their ability to work for specified periods of time.

This is a condition of existence common to all workers, not less to those who wear white collars and receive salaries than to those who wear overalls and receive pay envelopes. The boy leaving school at the age of 16 or 17 searches at once for an employer. There is nothing else he can do. His father does not own a “place of business”. Neither do his relatives nor his friends. Nor is there any way in which he can start a business of his own. There are exceptions, it is true, but in general the youngster leaves school and works all his useful life for some other person and lives through the years on wages.

So wages are very important to him and if unemployment causes his wages to stop, or if they become reduced or are not increased in times of rising prices, then he faces troublous times.

Yet the worker does not give to wages the thought and consideration which their importance obviously urges. That is because he is subjected to mental conditioning. He picks up his newspaper in the evening to find that world affairs are detailed and analyzed without reference to wages. He turns on the radio or television and gets lengthy periods of sports, popular music, plays and other things but not wages. Perhaps he goes to a movie house, to see a love story, a mystery, a Western or some other type of film, in which the characters all seem to live in some manner that precludes the existence of wages. On Sunday he takes himself to church to become removed to heights so lofty that the very thought of wages could only be disturbing if not blasphemous. There is a stigma attached to wages. The subject is dull and boring. Wages are not to be discussed except to reveal that they are an incontestable condition of existence for workers, but must be taken in modest sums.

How could the matter of wages be treated otherwise? All the main sources of information and entertainment are owned by the capitalist class, and these gentry are hardly likely to allow them to be used to call sympathetic attention to the wages question or to be critical of the system of wages payment. They like the wages system and they like wages to be low. It is from this state of affairs that their privileges and luxuries emerge. And they know that the more the minds of the workers are directed into channels remote from wages the less attention will they give to wages, and this can react only to the benefit of the employers.

But in spite of these diversionary activities, which attain a great deal of success in keeping them passive, workers do give attention to the question of wages. The pressures resulting from their status as wage workers, particularly the constant readiness of the employers to use every opportunity to lower their level of existence, compels activity in their own interest, even though this activity is all too reluctant and lacking in depth.

Over the years working people throughout the world have employed a variety of methods in the hope of improving their living conditions. They have petitioned Parliament, supported candidates for office, organized political parties. They have paraded in the streets, erected barricades and fought against police. But, most important, they have organized in trade unions which have provided them with their most effective weapon, the strike.

The trade union exists to protect and improve wages and working conditions. It engages in a number of other activities most of which are worthless, sometimes harmful. Because its members are not politically informed, it often allows itself to be used as a stepping stone to office by aspiring politicians. Indifference and apathy amongst its members sometimes lead to racketeering, cases of this kind recently being played up prominently in the daily press. But when all these things are taken into account, the real worth of the trade union must not be overlooked.

It seldom happens that a worker by himself can approach an employer and obtain an increase in wages. Workers in certain specialized types of employment may be able to do this, but not the average worker. He would be more likely to find himself on the street searching for another employer. Workers may influence their wages and working conditions only by collective effort and only by being in the position to stop working if their demands are not met. The ability to withhold their services is a weapon in their possession. It is the only final logic known to employers. Without it wages tend to sink below subsistence level. With it a substantial check can often be placed on the encroachments of the employers and improvements both in wages and working conditions can be made.

The strike is not a sure means of victory for workers in dispute with employers. There are many cases on record of workers being compelled to return to work without gains, sometimes with losses. Strikes should not be employed recklessly but should be entered into with caution, particularly during times when production falls off and there are growing numbers of unemployed. And it should not be thought that victory can be gained only by means of the strike. Sometimes more can be gained simply by the threat of a strike. Workers must bear all these things in mind if they are to make the most effective use of the trade union and the power which it gives them.

But, above all, the workers, besides making the greatest possible use of the trade union, must also come to recognize that even at their best the unions cannot bring permanent security or end poverty .These aims cannot be gained within the limits of capitalist society .When the workers have raised their sights high enough to envisage a society where there can be no conflict over wages, and where each will contribute to the production of wealth according to his ability and receive from the produce according to his needs, they are thinking of a goal that can be gained only after they have become organized into a political organization having for its object the introduction of Socialism. Such an organization is the Socialist Party.

Depression

IT IS a long time since the last great trade depression. Younger people will have little or no clear recollection of it. It occurred between 1929 and 1939, coming to an end after the outbreak of the second world war. The period was known as the Hungry Thirties. At that time there were something like a million unemployed in Canada, three million in Britain, six million in Germany, eleven millions in the United States. In 1934 it was reported that there were between 80,000,000 and 100,000,000 unemployed at that time throughout the world.

Even Russia, where unemployment was claimed by its supporters to have lately been abolished, was affected by the depression and had to cope with growing numbers of unemployed. And wherever it existed, unemployment, then, as now, deprived its victims of the sources of life other than the limited means made available through charitable groups and government agencies.

The world’s warehouses were filled with goods, the world’s workers were in want and the statesmen were helpless. Bennett of Canada, who rose to power in 1930 promising to end the depression, was ushered out of power in 1935 leaving 1,341,000 of the electorate on relief.

Roosevelt of the United States called to his service the greater part of the alphabet and won the hearts of the American people – but failed to end the breadlines. Hitler in Germany blamed the evils suffered by his countrymen on the victors of the first world war and he fed the German workers national pride, red banners and brown shirts – to go with their black bread and sausages. The Labour Party of Britain, which came on the scene to bring shelter to the underdog from the storms and stresses of modern life, became, after a quarter of a century without accomplishment, an unheroic victim of the 1930’s, broken by a Labour Government measure designed to worsen the living conditions of large numbers of workers.

And so it went on. Wherever one chanced to turn, the story could be told in much the same terms. It was a time of bleakness and want, anger and upsurge, fed upon by demagogues and mountebanks and turned in directions that brought no clear thought, much worthless and harmful effort and nothing of benefit to workers who were willing simply to serve as followers. Children spent their childhood improperly fed and clothed and lacking in playthings other than those that were whittled from wood by their fathers or fashioned from rags by their mothers. They entered schools and came out again, products of an educational system that shed no light on the desolation surrounding them. They approached young adulthood with nothing better to hope for than permission to enrol on the breadline without being subjected to the humiliating impertinences of petty officials. They feared to become married because marriage carried responsibilities which they had no way of meeting, as was carefully pointed out to them by the guardians of society. Those who became married despite these cautions found the stern visage of authority hovering over them, fearful lest they add to their numbers and increase further the burdens the nation was already groaning under!

The passing years, particularly the dozen recent years of work and wages and television sets, have dimmed the memory of the Hungry Thirties. For most people the angry insistence that something be done has given place to a placid acceptance of things as they are. That there can be another depression is a thought they will not entertain. They feel vaguely that everyone learned a lesson from the last depression, that people will not stand for another one; that in any case the world’s governments have taken measures or will take measures to prevent another from occurring. What lessons were learned and what measures have been taken or will be taken to prevent depression, these are matters which the average person hesitates to discuss – the blunt and gloomy truth being that his views in this connection are simply the product of wishful thinking.

It is a fact that the average person learned no lessons that matter from the last depression. It is also a fact that the politicians, the statesmen and all those on whom they depend for impressive thoughts, have failed to prove themselves better informed. The reasons are not hard to find. The average person has not made the slightest attempt to learn about depressions, and the official representatives of society, if they have made a study of the subject, have not come up with knowledge they are prepared to impart or act upon; for if they have discovered anything they have discovered that such knowledge can provide no help in preventing depressions and nothing sensible that can be used to encourage the average worker to continue his approval of the existing form of society; and since these people are committed to the preservation of present society without important changes they are obliged either to remain silent or ask people to retain confidence, trust in providence, or engage in other childlike pastimes.

There is no treatment for depressions that can bring lasting and beneficial results for the mass of the people while retaining the present order of society. That is why the brightest of capitalism’s defenders have nothing to offer on the subject but nonsense. The trouble is that capitalism is not a system that can concern itself about the needs of people and how best to satisfy those needs; it is a system in which goods are produced in order that capitalists may obtain profits; and when a situation arises in which these goods cannot be sold profitably, they are retained in warehouses whether or not there are people in need. This was the situation that prevailed during the Hungry Thirties; vast quantities of wealth decaying with passing years, vast numbers of people in constant and serious need – and not a government anywhere in the world that knew what to do about it!

Capitalism is by nature a chaotic form of society, often in the throes of stagnation and never free of misery. To end the fears, uncertainties and horrors of modern life requires the establishment of a system of society based upon the common ownership and democratic control of the means and instruments for producing and distributing wealth by and in the interest of society as a whole. This is a task to which you should give immediate thought and action.

Politics

EVERY so often the worker is invited to the polling places to elect a government for the term to follow. At such times he is an important person – the salt of the earth, the backbone of the nation, the mainstay of civilization. With the compliments of this or that political party his baby is kissed, his hand shaken, his back is slapped, his ego is catered to and the floodgates of oratory are opened to deluge him with emotion-packed words arranged to suggest that they mean something. Whatever his wishes may be – from the distant moon to the lowly carrot – they shall be granted.

It is a beautiful and inspiring sight. Men of stated worth, whose talents and virtues are repeatedly affirmed in all the important journals, imploring that the worker deliver his vote to them. Billboard signs, newspaper advertisements, radio and television programmes, garden parties, mass rallies, volumes of verbiage, all designed to ensure that he does the right thing. And he does.

Then comes the morning after. The signs are taken down. There is room in the important journals for more sporting news. The candidates congratulate each other. The oratory is ended.

The babies are unkissed except by their mothers. The moon fades with the dawn, but still hangs high. The carrots remain in the stalls. And the worker turns up on the job at the usual time to continue the business of working for wages.

All is normal again and one of the contending political parties has received a mandate from the electorate to keep it that way.

That’s how it goes. Lower income taxes become a substitute for higher wages. Increased old age pensions struggle to keep up with higher prices. A national health plan takes the place of local and company plans. Measures of little merit replace measures of little merit.

It doesn’t matter what condition the world is in. There may be a boom, a depression, or a war. There may be masses of people overworked, underfed, or dying violently. There is no shortage of politicians, amply provided with funds, preying on the gullibility of the populace by insisting that there is nothing wrong with society that cannot be cured by a little patchwork here and there. They may make their appeals to “the People”, or to “Labour”. They may in some cases believe the things they say and they may if elected bring into effect some of their promises. But however impressive and down to earth their efforts may seem, they never succeed in making the existing system of society fit to live in except to the parasite class and their principal protectors and bootlickers.

The game of politics, for all the sham, the vaudeville, the bombast, the empty promises so often associated with it, is a serious game. Vast sums of money are poured into it and these sums are not provided by the workers. The workers are not usually well supplied with spare cash and they are not in any case very much interested in politics. Their interest is limited mainly to giving ear to the commotion created at election time and deciding in favour of the candidates they think have given the best performance. The vast sums of money that are used to din from all directions the superiority of certain programmes, policies and candidates are provided by the property-owning class, the capitalist class, and they are not provided because of any thought that in this way the interests of society may best be served; they are provided in the expectation that only their own interests will be served, even though these come into serious conflict with the interests of society.

The capitalists have special material interests that cause them to have differences among themselves and these differences result in the existence of two or more political parties in most countries. But in one thing above all others they are united and that is in their support of parties that stand first of all for the continued existence of capitalism. They are prepared to sanction a generous outlay of attractive promises and political horseplay for the approval of the workers, since it is necessary that this approval be obtained; but whatever the politicians do to get themselves elected they cannot hope to retain the support of the capitalists if they allow the suggestion to enter into their activities that capitalism is not the best of all possible systems of society. Needless to say, they arc careful to protect their sources of campaign funds.

From all this it must be clear that the capitalists are far more aware of the importance of political action than are the workers. They sponsor and finance vast campaigns to ensure that governments are formed that will protect their privileged position. So great is their interest that in all modern nations they control not only the government but also the greater part of the opposition. This leaves the workers with little of prominence to choose from other than the various parties which, with slight differences dictated by sectional capitalist interests, all represent the capitalist class.

But there is an alternative. It is not necessary for the workers to continue supporting parties that represent interests opposed to their own. They can when they choose look beyond the noise and deceit that draw their attention at present. It will require some interest in politics. It will require some thought and study – far more than is now shown. But every moment of it will be worth the effort, for it leads unerringly toward a system of society that will rid mankind at once and for all time of the terrors and uncertainties that are so much a part of working class life under capitalism.

Socialism is the alternative. Its introduction means a change that will make the world a fit place for humans to live in. Most people today oppose Socialism because they do not understand it and are influenced by the sneers and misrepresentations instigated by the beneficiaries of present society. Study and knowledge will change that attitude and will teach the workers that capitalism is not worthy of support no matter what party speaks in its name; that for them only Socialism is worthy of support and Social ism is represented only by the Socialist Party.