How we live and how we might live (3)

In his London talk in November 1884 William Morris admonished his hearers that if they wished to be honest, they would ‘call competition by its shorter name of war’. He was referring to the war that rumbles on at the very heart of capitalist society. To engage with our world, that war is something we have to track down and confront.

As noted in last month’s article, there is a growing awareness that the origin of modern crises like human-induced climate change, species loss and pollution have a single origin in the mechanics of a capitalist economy. We ask, therefore, what is capitalism? The answer we get, unfortunately, is usually an ideological one designed to obscure rather than reveal the system’s true identity. Often it is a paper-thin definition such as ‘capitalism is the private ownership of the means of production’. Dissatisfied with this, we might plunge into the tangled world of capitalist economic theory, with its abstract analyses of markets, money, scarcity, demand schedules, etc. Common descriptions of capitalism get abstract very quickly. However, we can start to address this question another way by putting some solid ground beneath our feet. We can start by asking: what is an economy? The answer, at the broadest level of generality, is that it has something to do with humans and how they relate to one another in society. So let’s start with humans.

The first thing we can say is that whatever real or outlandish claims we make about ourselves, one thing stands out: we are physical beings in a physical world. We have biological needs for food, clothing, shelter and social contact. These needs we must satisfy continually if we are to survive. Second, we don’t survive well on our own. We have always lived together in communities. Evolutionary biologists tell us that we are a social species and that we are evolved cooperators. We operate with high levels of trust and sociability. The bloke next to us on the tube train may be irritating, but we generally find ways of getting along together for our mutual convenience. This behaviour contrasts sharply with that of our nearest relative. Cram a random collection of chimpanzees into the confined space of a rush hour tube train and the result will be soaring stress levels and, ultimately, carnage. We are, in fact, hyper-cooperators. We cooperate with strangers and even with other species. Social media is bursting with videos of humans supporting each other as well as rescuing cats, elephants, dolphins, kangaroos, eagles, sloths – you name it.

Not only do we live together in communities but we also work together to create the things we need. Levels of economic dependence vary between human societies, but we have never lived by producing individually for ourselves and consuming only what we have individually produced. We have survived by dividing up tasks among ourselves which are required to produce the things we need, and then sharing out the results according to some agreed method. And that gives us a pretty good definition of an economy: an economy is the way we organise ourselves to collectively produce and distribute the things we need.

At different points in time and in different parts of the world people have organised themselves in different ways. Some of our societies have similar features to our own; others are remarkably, even bizarrely, different – so different, that if we didn’t have the published field research of anthropologists, we might have dismissed them as fantasies or as unworkable.

Employers and employees

So, what is a capitalist economy? How do we divide up tasks within it to produce and distribute what we need? Central to the organisation of capitalism is an apparently simple social relationship – one that is reflected across most of society. It’s so familiar to us that we rarely question it, yet it has enormous consequences for our lives. This is the relationship that exists between the roles of employer and employee, between those who buy labour power and those who sell it. It is the wages system. People can to a limited extent move between these roles, but the roles themselves are fixed. This is not a relationship that is central to all human societies, and in many, it does not exist at all, but its existence and its centrality are what define capitalism.

An important feature of this relationship is that employers and employees are mutually dependent. Neither can exist without the other. Eliminate one and you eliminate both. The relationship is held together through a process of exchange: labour power for money (wages). It’s a process of buying and selling. And this requires the existence in society of a system of individual ownership – private property. Like the employer/employee relationship itself, not all human societies are built on the institution of private property. Some, like those of immediate return societies, own everything in common. People who own things in common do not exchange them; they do not buy and sell.

We think of property in terms of the objects we own. But this can be misleading. Pick up and examine a mobile phone, for instance, and describe it thoroughly. It has a certain shape, colour, weight, design. It feels a certain way in the hand. It has a definite set of functions. However, no matter how carefully and minutely you examine it, you will find nothing about it that tells you it is someone’s property. Property is not a natural attribute of things; it is a social relationship between people, an agreement to behave towards certain objects in specified ways. And for those who don’t behave towards them as society demands there will be social consequences.

A capitalist society, therefore, gives us rights and powers over things that are agreed to be our property, but denies those rights and powers to others. We accept this arrangement because we have been born into a pre-existing system of property owners and we have learned its rules. Property relationships occur in several different kinds of society, but a property relationship that expresses itself centrally through the employer/employee relationship is unique to capitalism.

One major consequence of a society founded on a property relationship is that it isolates individuals, families and groups from one another and divides them into defined property units. We can think of these units as property bubbles. You live in your property bubble with the things that society agrees to treat as your property, and I live in mine. Property is transferred from one bubble to another by means of exchange. An arrangement like this creates a tension between our cooperative way of living and producing things, and our individual ownership of them. That tension manifests as competition.

The property-based employer/employee relationship is the source of most forms of competition we experience throughout our lives and occurs at many levels of society. Employees, who live by selling their labour power for a wage are forced to compete with one other for their income at job interviews. Those who have jobs often find themselves in competition with others for promotion. In the world of employment, every penny that an employer pays to their employees is a penny less for themselves and vice versa, a condition that sets up a competition for how the company’s income is shared out.

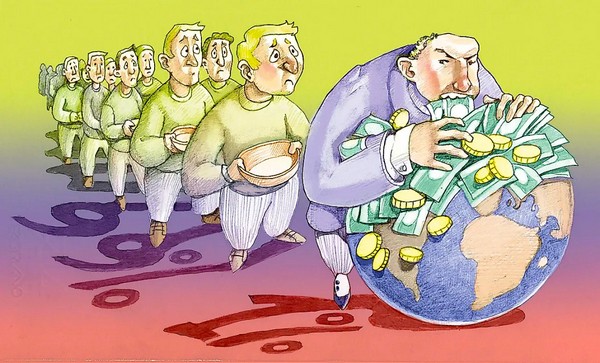

Businesses exist in their own individual property bubbles, causing them to compete with each other in the market for the money in consumer’s pockets. They lobby governments for legislation that will favour their business or their sector over that of others. Governments and businesses compete in our globalised economy for access to the world’s resources, markets, and trade routes. Governments negotiate and deploy their militaries to secure strategic advantage or forceful control over them. All this competition has its source in the fundamentals of a property-based employer/employee relationship.

Property-based competition

In his address, Morris reminded his hearers that, ‘Our present system of society is based on a state of perpetual war’, that is, on perpetual competition and perpetual conflict. When we compete over something as crucial as the means of life itself, or over a means of access to it – money – competition turns inevitably to conflict. In every kind of society, there are conflicts of interest, but the degree to which such conflicts exist and the degree to which they are resolvable depends on how extensively competition is built into a society’s structure. In capitalist economies, competition is universal. It is an objective feature of the system which gets turned ideologically into a positive value. It is taught in schools, it is often deliberately built into workplace relationships. It is a game among the wealthy and powerful that is played for high stakes. In our world, competition is impossible to eradicate without eradicating capitalism itself. Government reforms can do nothing. Even at their occasional best, they succeed only in providing temporary, partial and inadequate relief for competition’s many negative consequences. Competition and the conflict it creates are unending. Attack one problem here, and another breaks out elsewhere.

By its nature, capitalist property-based competition creates and exaggerates conflict at every level of society, and results in every degree of harm. It exists in the trivial and in the catastrophic, in the occasional awkward splitting of the cost of a restaurant meal, and in the devastation of vast mechanised warfare that rumbles on endlessly around the globe. Property-driven competition penetrates into the heart of the family. It erupts in arguments over domestic incomes; it tears family members apart over legacies. When relationships fail, it often turns acrimonious and ends up in the divorce courts. During disputes over pay and conditions the implicit competition between employer and employee breaks out into open conflict. Such conflicts can go on to have side effects which ripple out across society causing social disruption and individual tragedy as recently seen in the action taken by rail staff and junior doctors.

Capitalism is a cockpit of competing interests. It leads to clashes of all kinds. It provokes racial conflict and social ‘unrest’. It expresses itself in disinformation and propaganda wars. Competition over access to wealth and the status it brings drives people into conflict with the property system itself and leads to corruption, theft, embezzlement, fraud and many acts of violence and murder. Competing firms engage in industrial espionage and resort to strategies to put their competitors out of business and to extract money out of the pockets of workers. Governments attempting to protect or further the interests of companies within their territories introduce tariffs leading to trade wars, rising international tensions and diplomatic breakdowns. Conflicts over access to markets, resources and trade routes lead to threats and sanctions and ultimately to military actions and mass carnage.

When addressing the harm wrought by poverty and military conflict on our world we frequently point the finger of blame at surface causes such as government and business practice or at intangibles such as greed and ‘human nature’. We shy away from their real root causes which lie hidden in plain view in the operation of capitalism’s international property system. Emerging crises, such as climate change, loss of species and pollution get blamed on individuals: profit seeking capitalists, grasping politicians or bankers when, in reality, they are the inescapable consequences of capitalism’s property-based employer/employee relationship. Under present conditions, these problems are insoluble.

Next month we will look in more detail at how capitalism’s conflicted nature underlies these social ills.