How we live and how we might live

The year is 1884. It is a cold and foggy, late-November night down by the River Thames in London. Groups of people are hurrying along the road towards a tall Georgian building overlooking the river. As they arrive they are shown into an attached coach house, adapted for the occasion as a meeting room. They greet each other familiarly and shake hands with the house’s owner who is to give a talk titled, ‘How we Live And How we Might Live’.

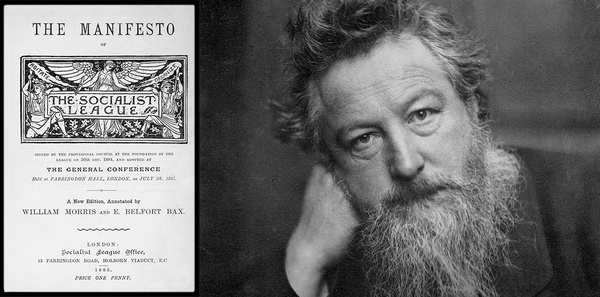

The name of the building is Kelmscott House and its owner is William Morris, a man widely admired as an artist-designer, a publisher, a printer, a founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement, a novelist and a poet. To his visitors, however, he is a revolutionary socialist. So, on this evening, Morris rises, and begins his address:

‘The word “Revolution”, which we Socialists are so often forced to use, has a terrible sound in most people’s ears, even when we have explained to them that it does not necessarily mean a change accompanied by riot and all kinds of violence, and cannot mean a change made mechanically and in the teeth of opinion by a group of men who have somehow managed to seize on the executive power for the moment.’

Morris’s opening remarks are not directly connected to his main theme. It seems he is issuing a challenge. He proceeds carefully but uncompromisingly, laying out his views on the nature of revolution. He warns:

‘…people are scared at the idea of such a vast change, and beg that you will speak of reform and not revolution. As, however, we Socialists do not at all mean by our word revolution what these worthy people mean by their word reform, I can’t help thinking that it would be a mistake to use it.’

Revolution or reform? This is the challenge Morris issued to his listeners seated in his coach house that evening. They, like he were members of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), which, only a few months earlier, had declared itself to be a ‘socialist’. Political declarations, however, often ring hollow under examination, and Morris was aware that many of the Federation’s members, including its leadership, were committed not to ‘a change in the basis of society’, but to a programme of government reforms of capitalism.

Morris had recently arrived at a crossroads in his political development. And that was an issue for him. Revolution, he believed, was the way forward, and it was antithetical to reform. So, which route would the SDF take? Did he perhaps intend his opening remarks to sound out the membership on this matter? If he did, then the response came swiftly. In less than a month he and several others severed their connection with the SDF, and founded a new organisation, the Socialist League one firmly committed to the revolutionary aim of bringing about ‘a change in the basis of society’. Morris drew up its constitution.

Palliatives

Morris focused his talk in the coach house on the persistence of working class poverty, which despite some amelioration over the previous fifty years remained starkly visible on the streets of 1884. Why, he asked his listeners, was poverty still a thing? And what was the solution? Revolutionary socialists in late Victorian England commonly referred to government reforms as ‘palliatives’. It’s a term not often heard today in political debate. It cuts through the rhetoric and exposes reforms for the ineffective things they are. At best, they aim to alleviate some particular ill with which capitalism burdens wage or salary workers. Governments announce reforms with great fanfare, especially at election times. Once enacted into law, however, many reforms have a short lifespan. They persist for a few years, until they hit the next cyclical crisis in the economy, or until a new political party is elected with a different agenda. Promises get reneged upon, funding is cut back or withdrawn and eventually the entire programme gets buried under the rubble of the capitalist profit machine and party politics.

What now remains, for instance, of the Labour government’s 1999 pledge to reduce child poverty to below 10% of children? Governments threw a great deal of money at the problem, and despite an initial success, the programme failed to meet its target for 2010. From that time on child poverty began rising again until the programme was abandoned in 2015/6. Now little more than twenty years later, child poverty is worse than ever. Palliatives do not persist. And because they do not attack social problems at their root, problems quickly recur.

We are now 140 years on from when Morris gave his address. Poverty is no longer as visible to us on the streets as it was then. We no longer see people walking the pavements unshod or in torn and filthy clothes. Yet, it is far from invisible. No one can have failed to notice the growing number of homeless people these days on the pavements of British towns and cities. And today a great deal of poverty is hidden away. Yet if we look hard enough, we will find, for instance, that in 2023, three million people in the UK appealed to food banks for food relief. That’s one in twenty of the population who did not have enough to eat for some part of last year. According to UK government statistics, one in five, are in danger of food poverty. In the United States, the world’s richest nation, the number of people visiting food banks last year hit 26 million, one American in 13. Perhaps we should not be too complacent about the ‘progress’ that has been made since Morris’s time.

Taking a longer view, we can look back at the history of the UK. Since capitalism began to emerge in the late eighteenth century, levels of poverty have fluctuated over time. The numbers have sometimes been relatively high or relatively low, yet at no time in those two and a half centuries has poverty been eradicated. It has remained a persistent feature of working class life throughout. And this is the case not only in the UK, but in every developed capitalist nation on earth. Poverty is endemic to the capitalist system, and Morris’s question remains to be answered: ‘why’? Why, despite repeated attempts by governments everywhere to eliminate it is it so persistent and so universal? The literature on poverty and its elimination gives a clue. It is vast and international, yet perhaps the most interesting thing about it is that the solutions it proposes are uniformly superficial and reflect the political dogmas of those with power.

Poverty persists

Neoliberals confidently identify the source of poverty in blockages in the operation of the ‘free’ market. They point the finger at trade union action and large scale industrial bargaining, at minimum-wage legislation and ‘excessive’ welfare payments to the unemployed. If distorting influences such as these were removed they claim, the market would balance itself, and poverty would disappear. Poof! Gone!

For traditional conservatives, the origin of poverty lies in the decline in the family, and (condescendingly enough) in working class culture. Without a stable (heterosexual) family structure children are not properly socialised or educated. This leads to welfare dependency, loss of initiative and self esteem. It leads to crime as an alternative to wage working. And of course it leads to a loss of deference to necessary hierarchical structures.

Labourites and Social Democrats have historically seen poverty as a failure of government to provide sufficient regulation of the labour and housing markets and a lack of spending on public services and benefits. More recently they have ‘discovered’ that the poor lack ‘social capital’. Barriers to upward mobility are to be found in weak community ties and supportive organisations.

Building on these and other superficial analyses, nation after nation has applied sticking plasters on the problem. Yet poverty persists. Decade on decade. Relentlessly. And to the extent that government programmes have brought some relief to working people, their effects have been limited and temporary. The application of such programmes, however, costs money, and in periods of low profitability, they get jettisoned altogether and working people are once again abandoned to the mercy of an unstable market economy.

The Labour Party, which committed itself to eliminating child poverty in 1999, is now back in power. Keir Starmer, in his bid for the party leadership in 2020, declared that he would make tackling poverty a major commitment. By now, however, we know that when put to the test a great many political declarations ring hollow, and Starmer’s ‘commitment’ quickly became buried in the rubble of capitalism’s economic instability and party politics. Right now, British capitalism is sunk in one of its down phases, so it is unsurprising that no renewed commitment to eliminate child poverty appeared in the 2024 Labour Party Manifesto. During the election campaign, few Labour candidates spoke out on the issue. Once safely elected to their seats, however, the indignant voices of Labour back benchers have been raised against the leadership resulting in the first big ideological battle within the new governing party.

Priority for profits

In a delicious piece of political theatre, a brave Tory defender of working class living standards, Suella Braverman, devoted her first speech as an opposition MP, to raising the issue of the two-child benefit cap imposed by her own party in 2019. The aim of this benefit restriction according to Braverman was to ensure that the unemployed ‘make the same choices as those supporting themselves solely through work’. Decoded, this means it was intended to discourage the poor from having children. The policy, she declared had not worked. (Highlighting a Tory failure, it seems, is less motivating than stirring conflict within the Labour Party.) And so, in the name of ‘the family’, that sacred Tory shibboleth, it is suddenly now essential to repeal this wicked policy and – astonishingly! – end poverty in Britain for good! Starmer, however, is adamant that his government’s priority must be to restore profitability in the country before the next palliative is proposed. Why does this sound familiar?

So many social reforms have been introduced over the decades to eliminate the evils of capitalism. Apart from those that have little or no effect on profitability, only a few have proven to be of lasting benefit to workers, some have been detrimental, and almost all have been eventually watered down or abandoned. So Morris’s question returns, again and again: ‘Why’? Why do reforms fail to relieve the strains of working life? Well, here’s a thought. What if the source of these problems lies not in declining family values, in blockages of the ‘free’ market, in the failure of government regulation, in social exclusion, in greed, in self-interested politicians or in anything else of that kind? What if the source of the problem is to be found in something far more fundamental to the capitalist system – something as central to it as the wages system? What if the only solution to the problem of ‘How we Live’ is not reform but, as Morris realised 140 years ago, ‘a change in the basis of society’. Over the coming issues of the Socialist Standard we will dig down into this question.

HUD