What drives the capitalist economy

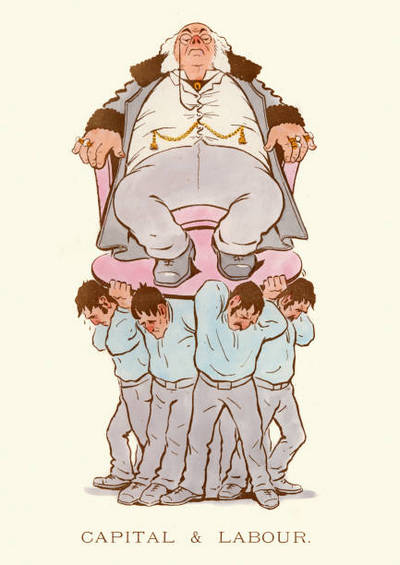

One thing that cannot change whilst capitalism lasts is the fact that workers, being forced to sell their working abilities to a capitalist by virtue of being alienated from the means of wealth production, will only be employed by the capitalist on condition that the value of what they are paid falls significantly below the value of their labour input – what they contribute in terms of their labour to the product in question. This surplus value is the source of the capitalist´s unearned income and is realised when that product is sold on the market.

This system cannot possibly allow that the workers should be entitled to the full fruits of their labour. A business, after all, is not a charity; it needs to secure what in economic parlance is called a financial return. The systemic need for a tiny minority to extract an economic surplus from the great majority makes it structurally impossible for all but this minority to live off an unearned income from what they invest.

By ‘need’ is not meant the desire on the part of those comprising this tiny minority to surround themselves with the trappings of ostentatious luxury. Self-enrichment is, in any case, more a want or a whim than a need. In this regard, Victor Hugo´s famous observation that ‘The paradise of the rich is made out of the hell of the poor’ could very easily be misconstrued. It is not out of some particularly malevolent, or sociopathic, disregard on the part of the rich for the plight of the poor (though, doubtless, one or two individuals might well live up to this caricature) that we have a problem of working-class economic distress.

Unfortunately, this way of thinking lends itself to an all too facile – not to say, downright misleading – approach to resolving that problem. According to it, this problem essentially boils down to the moral shortcomings or defects of particular individuals or groups. Thus, it is because of greedy bankers or heartless or uncaring corporations that we have homeless itinerants, grossly polluted waterways and third-world-type sweatshops in which impoverished machinists toil for a pittance in a gruelling twelve hour working day. If only they were more caring, more concerned, these kinds of issues would recede, if not disappear altogether. It is not difficult to see how such thinking can play directly into the hands of those fervent exponents of modern ‘philanthro-capitalism’ and its curious belief that the way forward is to harness old-fashioned patronising capitalist philanthropy with the skills and corporate insights of capitalist entrepreneurship.

The point is that whatever may personally motivate the individual capitalist this is really incidental or secondary to what actually drives the system they conspicuously benefit from. The spectacular personal fortunes of the minority are more the by-product of, than the objective behind, the systemic extraction of economic surpluses from the majority. The primary purpose of this extractive – or more precisely, exploitative – process is, rather, the capitalisation of those very economic surpluses that such a process gives rise to. Transforming them into capital ensures a future flow of such surpluses. It is a cyclical process that repeats itself over and over again and it is essentially what has delivered the grotesquely unequal world we live in today.

In capitalism, market competition between enterprises forces each enterprise to seek out ways in which it can enlarge its share of the market at the expense of its rivals. This is not a matter of choice. Just as the worker is economically compelled to seek paid work in order to live in a society in which almost everything comes with a price tag, so capitalists are economically compelled to become competitive (regardless of what her particular moral outlook on life may be). Failing to keep up with the competition means sooner or later, being squeezed out of the market by one´s more ruthless and single-minded competitors. In other words, being bankrupted, or maybe asset-stripped and gobbled up, by the latter.

To keep up with the competition you need to hold down your operating costs (and, in particular, your wages bill) as far as practically possible and, at the same, time boost your revenue – the money you receive when you sell your commodity on the market. Boosting your revenue typically involves trying to undercut your competitors pricewise. In theory, this should bring in more customers for you and at their expense. However, being able to reduce your prices (and keep financially afloat) requires investing in more productive technology, among other things.

That is where the need to have an economic surplus at your disposal is all-important. It is the very lifeblood of the system itself in much the same way that a vampire depends on the blood of its victims for its own sustenance. It allows you to finance the replacement of outdated and possibly worn-out equipment with new state-of-the-art machinery. Increased productivity means being able to reduce your unit costs – and hence your prices – below what your competitors can afford. The desired effect is to push them out of the market altogether, allowing you to capture their share of that market.

It is a ruthless game in which no prisoners are taken, and no holds are barred. If you don’t do to your opponents what this dog-eat-dog system bids you to do then you can be certain they will try to do it to you. It’s a case of ‘natural selection’ transferred to the economic domain.

In summary, then, businesses survive in the particular niche they occupy only by constantly striving to expand. Driving this whole process is the accumulation of capital out of surplus value.

ROBIN COX