Ideology and Revolution pt.2

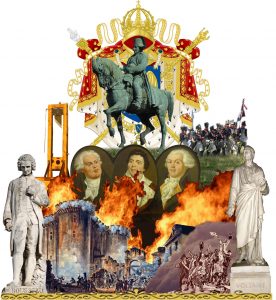

In the second part of this three-part series we look at the French Revolution

On the 4th April 1727 a leading French intellectual was present at the state funeral of Sir Isaac Newton in London. His name was Voltaire and what he found most impressive about the grand occasion was that although Newton was born a commoner his work had gained him such prestige as to warrant so high a national honour. Such a thing could never have happened in France at that time where only members of the nobility could hope to provoke such national recognition. This was a testament to the complete political domination of the English bourgeoisie who, after their revolution in the 1640s, had fought off an attempted counter revolution in 1688 and installed a constitutional monarch, an act of religious tolerance, free trade and even a ‘bill of rights’; something which the French middle class could only dream of. The new English ruling class embraced the symbiotic relationship of science and technology which was soon, through the immanent ‘industrial revolution’, to make them far wealthier than many of the petty European feudal monarchies. Isaac Newton became one of the first icons of the intellectual movement that turned its focus from religious faith to scientific reason in what we now call ‘The Enlightenment’. Newton presented society with a universal natural mechanism that had the potential to explain everything – including, in the hands of philosophers and political radicals, the perceived intellectual and moral progression of human cultural activity through history. It was to be the French intellectuals who were to transform this radical philosophy into a political ideology with which to fuel their own bourgeois revolution.

We have seen that it was the Protestant Reformation that enabled the English bourgeoisie to intellectually challenge the might of reactionary international Catholicism and which, in turn, informed the ideological propaganda used in their revolutionary struggle with their king. In France the Reformation was only ever partially successful and eventually almost entirely succumbed to the ‘counter reformation’. As a result the capitalist mode of production was continually handicapped by the very same feudal economic relationships that had so frustrated the English middle classes in the first part of the 17th century. This underlying class struggle was simmering and waiting to burst into revolution in France by the mid to late 18thcentury. As we have seen, it was the French intellectuals’ use of Enlightenment philosophy which was to reflect this remorseless economic and political tension. Foremost among these was Dennis Diderot’s Encyclopaedia which attempted the complete reformulation of knowledge through an enlightenment perspective. Together with writers such as Rousseau and Voltaire they began work on this monumental undertaking which was immediately recognised as a threat to the establishment by those who sought to defend the ‘Ancien Régime’. Another surprising element that served to weaken the paradigms of continental Catholicism came from a most unlikely source. Portugal had always been devout and, like its neighbour Spain, a bastion of reactionary autocracy. In 1755 a mighty earthquake hit its capital Lisbon destroying most of the city including many churches together with their congregations. A reciprocal tsunami augmented the devastation and death toll. Many believed this to be a breach of the covenant with the Christian god and served to seriously weaken belief in traditional religion and the social structures that went with it. All of these uncertainties, new intellectual paradigms and the manifest injustices of feudal autocracy were about to find their political expression as part of the explosion that was the French Revolution.

Action replay

It all started, as almost an action replay of the English revolution, when the French king was forced to call a parliament (Estates General) to deal with a financial crisis. France was near bankruptcy as a result, ironically, of Louis XVI helping to finance the American republican struggle against England. This parliament was composed of three ‘estates’: nobility, clergy and the commons. Although the deputies of the commons represented over 90 percent of the French people they only had a third of the votes, the other two thirds belonging to the nobility and clergy. This made it inevitable that they would be out-voted by the other two estates on most issues of contention. Upon being called to Versailles the members of the commons produced a book of grievances which addressed, together with many other problems, this profoundly anti-democratic arrangement. Unsurprisingly the other estates prevaricated and the commons lost patience and proclaimed itself as a National Assembly which represented the entire population of France and on its return to Versailles, some days later, to begin its work the delegates found themselves locked out of their former meeting place. Undeterred they proceeded to the nearest large interior space within the massive palace complex (a tennis court) where they took an oath not to separate until they had produced a political national constitution.

Thus began the revolution on 20 June 1789. Despite a provocative build-up of reactionary military forces the Assembly quickly got to work abolishing feudalism and producing a Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (again very reminiscent of the English parliament’s Petition of Right and then its revolutionary ‘Grand Remonstrance’ of some 150 years before). In Paris, meanwhile, the decades of oppression of the poor had exploded into violence which culminated in the storming of the Bastille and the subsequent arming of the ‘sans culottes’ (proto working class) who were to defend the revolution against both traitors within the country and then to fight the revolutionary wars against the other nations which sought to destroy the new regime. The French bourgeoisie originally, as had the English, wanted a constitutional monarchy rather than a Republic but when Louis, like Charles I, was proven a traitor he was executed. By now the Assembly had moved to Paris where it came under the influence of a radical republican group (the Jacobins) and their most prominent member Maximilien Robespierre who, arguably, took the revolution in a direction that the moderate members of the bourgeoisie had never intended and which certainly did not correspond with the values of the Enlightenment.

These radicals would have been unable to take control of the revolution without the confluence of a series of events; civil war, international war, inflation and sectarian rivalry all contributed to what we now call ‘The Terror’ and the reign of Madame La Guillotine. In some ways this goes to prove that the ideology of the Enlightenment was, at best, only an idealistic aspiration and, at worst, merely empty propaganda to motivate those who did the fighting. Certainly when Napoleon Bonaparte came to power during a coup d’état in 1799 and subsequently ‘exported’ the revolution to most of continental Europe it was seen eventually for what it really was – an empire of exploitation and plunder. Oliver Cromwell had preceded Napoleon in this by his violent imperial activities in Ireland and both individuals represented the realities of bourgeois rule, stripped of its high minded rhetoric.

Since the days of these capitalist revolutions many millions of workers have continued to kill and be killed in the name of high ideals such as liberty, fraternity and equality. This does not, of course, invalidate these ideals and the integrity of those like Rousseau and Diderot who believed in them but, like the radical Christian ideals of the Puritans, they captured the ‘zeitgeist’ of their time, and as such, were open to manipulation by the powerful. That power, in the end, derived not from ideals but from economic and political forces which were little understood at that time. Both the French and English revolutions had the same result – the coming to power of the capitalist class despite the use of seemingly opposite ideologies (philosophical reason as opposed to religious faith); dialectically speaking such ideas are taken up because they seem to contain, however vaguely understood, antithetical elements with regard to the prevailing paradigms that rationalise the existing system. Such ideas always find an audience because of the oppression and exploitation necessary to sustain any private property system. These ideas are catapulted into the political spotlight when economic and historical circumstances make revolutionary change inevitable. Socialists, with the invaluable help of Karl Marx, have understood this for over a hundred years but, ironically, this political insight also fell victim to the manipulation of a new ruling class – namely the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution. Does this imply that Marxism/socialism is merely just another form of idealism that can be manipulated and used as propaganda by power elites?

In part three we investigate the relationship between the revolutionary events in Russia in 1917 and the political theory of socialism and what both owed, if anything, to the Enlightenment.

WEZ