Getting the betrayal in first

‘One day, it seems, Tony Blair is likely to be in Number Ten and, therefore almost certainly, will be in confrontation with public sector workers. He has, in Neil Kinnock’s rueful phrase, got his betrayal in first’ (Andrew Marr, Independent, 19 April 1995: bit.ly/3bIRiVY).

Marr was writing about Tony Blair when Leader of the Opposition, but he could just as well have been writing about Sir Keir Starmer today.

We can’t claim that Labour leaders have learnt nothing from the experience of the various Labour governments that there have been. Elected to power on promises to improve the lot of workers and to help trade unions achieve this, every single Labour government has ended up opposing strikes and insisting that priority be given to profit-making (some have done worse, imposing wage freezes and prosecuting strikers). In that sense they have betrayed the unions who supported them and workers who voted for them.

Starmer sees himself as the Prime Minister of a ‘government in waiting’ and knows that, in government, he too will have to resist wage demands that threaten profit-making. In sacking one of his shadow cabinet for going on a picket line without permission, he was sending out a clear message that he was fully prepared to do this.

Starmer sees himself as the Prime Minister of a ‘government in waiting’ and knows that, in government, he too will have to resist wage demands that threaten profit-making. In sacking one of his shadow cabinet for going on a picket line without permission, he was sending out a clear message that he was fully prepared to do this.

Sharon Graham, the General Secretary of Unite, reacted by declaring that the sacking incident showed that ‘the Labour Party was becoming more and more irrelevant to working people’. But was it ever relevant? The question that should be asked is not ‘What has the Labour Party done for us’ but ‘What has the Labour Party done to us?’

Starmer is going to behave in office as previous Labour Prime Ministers have. So what did they do to us?

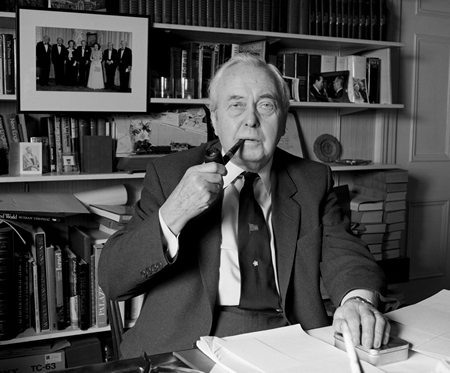

In 1964 after what the Labour Party called ‘thirteen years of Tory misrule’ they got in and Harold Wilson became Prime Minister. His government started by honouring some of its promises. It abolished prescription charges and a national plan was drawn up. Then an economic crisis broke out. The pound was devalued; it maintained its face-value in people’s pockets but its purchasing power diminished due to the prices of imported goods going up. Prescription charges were re-imposed and the national plan became a scrap of paper.

In 1964 after what the Labour Party called ‘thirteen years of Tory misrule’ they got in and Harold Wilson became Prime Minister. His government started by honouring some of its promises. It abolished prescription charges and a national plan was drawn up. Then an economic crisis broke out. The pound was devalued; it maintained its face-value in people’s pockets but its purchasing power diminished due to the prices of imported goods going up. Prescription charges were re-imposed and the national plan became a scrap of paper.

From then on, it was downhill all the way as these contemporary headlines illustrate (Ray Gunther was the Minister of Labour and George Brown the Secretary of State for Economic Affairs):

- Mr Gunther Condemns Dock Move by Strikers (Times, 20 October 1964)

- Britain’s Attitudes Outdated—Premier. Country ‘cannot afford strikes’ (Guardian, 25 February 1965)

- Profit Motive as Test of Efficiency. Mr Brown’s Reply to Directors. “Government Not Anti-Business” (Times, 22 May 1965)

- Wilson Hits at Rail Go-Slow (Observer, 18 July 1965)

- Wage Restraint Vital in 1966—Premier (Financial Times, 1 January 1966)

- Folly To Press For Big Wage Rises—Chancellor (Financial Times, 18 May 1966)

- Ministers Hint At Permanent Pay Curb (Observer, 18 September 1966)

- Government Embraces Profitability (Guardian, 23 November 1966)

- Standard of Living ‘Must Fall’. Mr Gunther on Last Chance (Times, 29 March 1968)

While the need for profits was accepted, wage demands were opposed. The Labour MP, Harold Lever (later a minister and then a Lord) explained very cogently why:

‘Labour’s economic plans are not in any way geared to more nationalisation; they are directed towards increased production on the basis of the continued existence of a large private sector. Within the terms of the profit system it is not possible, in the long run, to achieve sustained increases in output without an adequate flow of profit to promote and finance them. The Labour leadership know as well as any businessman that an engine which runs on profit cannot be made to move faster without extra fuel’ (Observer, 3 April 1966).

This is still the situation today. A future Labour government under Starmer will have to work (as one under Corbyn would have had to) within the same framework of ‘the commanding heights of the economy’ being in the hands of private profit-seeking enterprises, whose necessity to make a profit must be recognised. And will be.

The Wilson Labour government was voted out of office in 1970 but Labour came back in 1974, briefly under Wilson, then under James Callaghan. The 1974-79 Labour government was just as much a disaster, provoking the notorious 1978/9 Winter of Discontent. Troops (let alone agency workers) were called out to break strikes by Glasgow refuse collectors (1975), air traffic control assistants (1977), firefighters (1977), naval dockyard workers (1978), and, finally, NHS ambulance workers (1978).

The Wilson Labour government was voted out of office in 1970 but Labour came back in 1974, briefly under Wilson, then under James Callaghan. The 1974-79 Labour government was just as much a disaster, provoking the notorious 1978/9 Winter of Discontent. Troops (let alone agency workers) were called out to break strikes by Glasgow refuse collectors (1975), air traffic control assistants (1977), firefighters (1977), naval dockyard workers (1978), and, finally, NHS ambulance workers (1978).

In 1979, as a reaction, the Tories under Thatcher were elected and 18 years of Tory rule followed. Tony Blair became leader of the Labour Party in 1994 and immediately set about making it ‘electable’. This involved abandoning even the long-term paper commitment to changing private capitalism into state capitalism (Clause IV) and fully accepting the profit-seeking market economy. As Blair told the Financial Times (11 June, 1994):

‘We want a dynamic market economy. It is not merely that I, as it were, with hesitation acknowledge that this is the way we have to go. I say that it is positively in the public interest to have a dynamic market economy.’

Labour, under Blair, was returned to office in 1997 and, external conditions being relatively favourable, did not make such a mess of presiding over the operation of capitalism as Wilson and Callaghan had. The main reforms that the Blair Labour government introduced were constitutional rather than economic and so did not impinge on the operation of the profit-driven capitalist economy. The anti-union laws enacted under Thatcher were not repealed and are still in force today.

There is no reason whatsoever to suppose that a Starmer Labour government would be any different from previous Labour governments. The reason why these failed and ended up giving priority to profits over wages was not because its ministers were dishonest or incompetent or not resolute enough. It was because they had set themselves an impossible task. The very nature of capitalism means that it cannot work, or be made to work, in the interest of those obliged to work for wages. It is a profit-making system that can work only in the interest of the profit-takers, whose source of income is the unpaid labour of the wage-working class. Prior to the Blair government, Labour leaders had to learn this the hard way. Starmer, like Blair, knows that, for the reasons explained by Harold Lever in 1966, a future Labour government would have to let capitalism work this way. At least he is being candid about his intentions. Workers and unions should take heed.

ADAM BUICK