David Graeber’s False Dawn

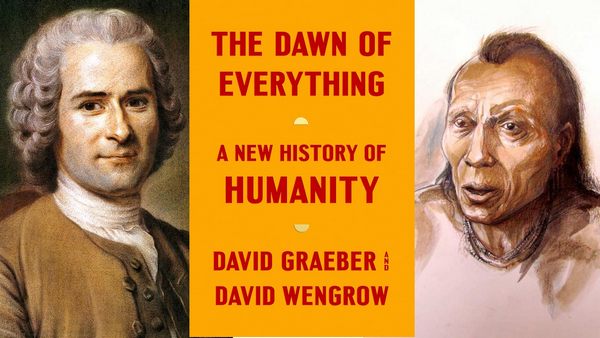

Graeber and Wengrow’s new book, The Dawn of Everything, is making waves. Its cover may not be sitting, face out, on the shelves of all the high street bookshops, but it is gathering a lot of positive reviews in both the left- and right-wing press. For a book written by a prominent anarchist, getting any reviews at all in the conventional media is quite a feat in itself. So, what is going on? Well, for one thing, The Dawn of Everything sets out to challenge the conventional narrative of human origins – or claims that it does. And since the conventional narrative in anthropology is one which, since the 1960s has tended to favour left-wing interpretations of ‘human nature’, it is no surprise the right has welcomed it.

The Dawn of Everything is a big, fat book, some 500-plus pages in length. It is teeming with fascinating accounts of recent archaeological findings. And it is worth reading for this alone. Anthropologists are not great popularisers of their work, and much of the information contained here is normally only available on the shelves and stacks of university libraries. As the subtitle of their book tells us, however, Graeber and Wengrow (G&W) are not merely interested in informing the public of these new findings, they are attempting nothing less than A New History of Hu-manity.

Their book opens with a historical survey of the way in which the debate about human origins has been framed in Europe. In essence, it’s an argument between those who, like Jean-Jacques Rous-seau, view ‘human nature’ as essentially co-operative, and our early human relations as egalitarian, and those who, like Thomas Hobbes, regard us as competitive creatures, and conceive of our early existence as a ‘war of all against all.’ These claims, of course, have distinct political alignments. For left-wing Rousseauists, humanity is best suited to living in an egalitarian society, while for right-wing Hobbesians, no degree of human flourishing is possible without a restraining dominance hierarchy. Numerous variations on these two opposing myths have emerged over the centuries, but they have continued broadly to shape the debate.

Egalitarian hunter-gatherers

In 1966, however, a milestone was passed when the first ‘Man the Hunter’ symposium of hunter-gatherer specialists was held in Chicago (the name of the symposium reflected the patriarchal as-sumptions still prevalent in the anthropology of that time). As researcher after researcher took to the podium, a radical picture of hunter-gatherers began to emerge. Above all, the evidence showed that hunter-gatherer peoples had notably egalitarian features, and there was a subset among them that was hyper-egalitarian in virtually all aspects of their social lives, including rela-tions between men and women. This suggested that humanity itself had egalitarian origins. Within the academic discipline of anthropology, at least, the Hobbesian view of humanity’s hierarchical nature and beginnings had been blown clear out of the water.

Around the turn of the millennium, this view of hunter-gatherers was given new theoretical depth by Christopher Boehm in his 1999 book, Hierarchy in the Forest. Boehm pointed out that the Rousseauist and Hobbesian narratives both contain elements of truth. Human beings are undoubtedly capable of seeking to dominate others, but they are also innately predisposed to resist being dominated, and wherever possible will band together to repulse those who would subordinate them. In Boehm’s view, whether a society became egalitarian or hierarchical depended on whether the material conditions within that society advantaged those with a will to dominate or those who resisted being dominated. Our early societies were egalitarian, he argued, because the conditions they lived under favoured coalitions which could resist domination. One example of such a condition was the invention of projectile weapons which could be used by everyone, large or small, male or female, to undercut the physical strength possessed by alpha males. This resulted in a state of reverse dominance, or counterdominance as it is now more commonly called.

Evolved cooperators

Boehm’s argument set the scene for a revolution in anthropology. The next step was taken by Sarah Hrdy, in her ground-breaking 2009 book, Mothers and Others. Although Boehm had argued for egalitarianism among males in early human societies, he had made the assumption, common at the time, that in early societies males had dominated females. Hrdy pointed out that there were biological grounds for not taking this assumption for granted. Humans differ from their great ape cousins in one very noticeable respect: they give birth to big-brained babies. Human brains including the brains of infants gobble up calories at a furious rate, and human children mature slowly, remaining dependent on their caregivers for many years. In the Machiavellian world of our close cousins, chimpanzees, with its alpha males and hostile, shifting alliances, no mother could or would trust her infants to another female and certainly not to a male. In the human world by contrast, mothers could not cope with feeding and bringing up their children alone. If humans were to survive, they would have to develop co-operative childcare arrangements, something we invariably see among egalitarian hunter-gatherer peoples. Among great apes, males are the leisure sex. The only contribution they make to the next generation is a dollop of sperm. In human societies, that was no longer feasible. Mothers needed help from their own mothers and from the rest of society, males and females alike. Humans, Hrdy argued, are evolved co-operators. We co-operate on a grand scale, and this requires the development of a great deal of trust. Numerous evidences that we are biologically wired to coordinate our activities exist. We see signs of it marked on our bodies, in our ‘co-operative eyes’, for instance. Whereas the eyes of our great ape cousins are round, and the sclera which surrounds their irises is dark, our eyes are almond shaped and our sclera are white. We can see immediately where some other person is looking and therefore what they might be thinking. It is hard for a chimpanzee to read much from the eyes of a rival. Humans on the contrary are extremely good at interpreting other people’s thoughts and reactions from their eye movements, a process known as intersubjectivity. Research has demonstrated that humans are capable of working out how someone is reacting to the way we are reacting to their reaction.

Strange synthesis

In The Dawn of Everything G&W set out to challenge this orthodoxy. Like Boehm, they propose a kind of synthesis between the Rousseauist and Hobbesian myths, but a synthesis of a rather strange kind. They argue that in fact there is no particular way in which our original societies organised themselves, that humans have always adopted a range of different social forms, sometimes egalitarian, sometimes hierarchical, and that we have done so purely out of choice. Graeber, in particular, had long been of the view that conditions of individual freedom can arise at any time irrespective of the economic context. Similarly he has denied that there exists any such real thing as culture, that there are merely individuals who are free to create their own identities. This suggests that Graeber believed that there was no value in attempting to overturn capitalism, since no society will ever be governed by a single principle. At best we should seek out liberated zones where community can assert itself.

For G&W, however, the ability to choose our own social structures is part of what makes us human. In support of this claim, they make several arguments in the course of their book. They point to a number of groups such as the Inuit that are known to vary their social structures seasonally. During one part of the year, they form hierarchical relationships in which, for instance, women are subordinated to men, and egalitarian ones during another. These relationships, according to G&W are chosen in a playful, carnivalesque spirit.

As an approach to understanding social organisation, this idea has multiple problems. Societies are rarely, if ever, the result of unified or even collective decision making. It seems hardly credible, for instance, that women would have playfully chosen to occupy a role subservient to men, or that one section of society should have placed itself freely and experimentally under the oppressive rule of another. To say that ‘society chooses’, means, at most, that some section of society with some material advantage over the rest has exercised a prominent influence over social relations. Class societies are cockpits of competing interests with built-in fault lines, and even classless, egalitarian societies are full of members whose desires and wishes come into conflict with one another.

A second line of argument that G&W advance in The Dawn of Everything is that in the last few decades, evidence has been accumulating which challenges the ‘standard’ view that we had egalitarian origins, or that hierarchical (class) societies emerged only with the onset of agricul-ture. In particular they turn to archaeological evidence from the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe (ap-proximately 40,000 – 15,000 years ago). This evidence includes, for example, the discovery of large-scale ‘ceremonial’ buildings and a number of ‘princely’ burials that contain artefacts which would have taken a great many hours of collective labour to produce.

Multiple problems

These arguments should be treated with care. G&W, for instance, have limited their examination of the evidence to only one small part of the globe, to Europe, which is conveniently the only area in which clear evidence for hierarchical society definitely exists during this period. They have also limited their view to the last 40,000 years, a relatively short, and relatively recent, period of time. If we go back beyond this period, evidence that could indicate the existence of hierarchical societies becomes vanishingly rare (which led one critic, Chris Knight, to point out that the book should have been titled The Tea Time of Everything). The authors attempt to justify their limited time frame by arguing that evidence before 40,000 years ago is scant and we cannot reliably know what was going on in this period. It is true that archaeologists have less evidence than they would like from before the Upper Palaeolithic, but is not negligible as G&W suggest, and with modern methods of analysis, a lot of information can be gleaned from it. Moreover G&W’s argument cuts both ways. If we take the view that the evidence we do have is unreliable, then we certainly can’t conclude, as G&W do in one of their most bizarre arguments, that because the physical appearance of individuals varied widely in earlier periods (several human species still existed side by side), we can simply assume that their forms of social organisation were also various and not necessarily egalitarian.

When setting out this evidence for hierarchical societies in the Upper Palaeolithic, the authors are careful not to tell their readers how extensive it is or how it compares with evidence for other forms of social organisation. As their review of it takes up a significant amount of space it is easy to get the impression that it is rather extensive, when in reality this is not the case. Covering a period of 35,000 years, for example, archaeologists have found no more than six ‘princely’ burials. More-over, as G&W admit (when they are not directly advancing their claims for hierarchy) the individu-als found in these burials show evidence of some sort of physical deformity making them difficult to interpret. It is not possible to conclude with certainty, therefore, that they indicate the existence of hierarchical or class societies at all. The meaning of big ceremonial buildings is also ambiguous as similar constructions have also been discovered in societies that are at least partially egalitarian.

There is a lot about G&W’s arguments throughout The Dawn of Everything that doesn’t add up. And their book presents other concerns as well. They tend, for instance, to suggest that anthropologists habitually ignore the evidence now available for hierarchical societies in Upper Palaeolithic Europe and cling to older egalitarian narratives. In reality, most anthropologists are very aware of this new evidence and in the last two decades have modified their views to take note of it. They have pointed out, however, that the balance of evidence is still in favour of predominantly egalitarian early societies. Instead of addressing the evidence for this claim, G&W go noticeably silent, preferring instead to poison the well by tossing aside such views as ‘Utopian’ or as ‘Garden of Eden’ narratives. Their treatment of Christopher Boehm’s Hierarchy in the Forest, is an example of their general attitude to the subject. Having presented a positive assessment of his theory of reverse dominance, they feign surprise and confusion at why he, like the majority of anthropologists, should commit to belief in human egalitarian origins. The answer is not hard to find by anyone who wants to find it. In his book, Boehm sets out explicitly the grounds on which he takes this view. As for the extensive work of Hrdy and others on co-operative childcare, G&W hand-wave this away in a single sentence. It is difficult to avoid the impression that the authors are trying hard to present themselves as pioneers, as edgy and iconoclastic rebels against the academic status quo.

Graeber’s dismissal of the idea of early egalitarianism is one that has a long history in his writing. Anyone who reads through the bibliographies of his earlier works, for instance, is unlikely to find reference to authors who have pursued this research. He has consistently refused to address it, and is notorious for accusing colleagues who have published reports of their fieldwork on egalitar-ian hunter-gatherers as having made it all up. At first sight, this seems a curious attitude. Knight has argued that it can be traced back to Graeber’s early experience of fieldwork in Madagascar where for specific historical reasons the state had dwindled in significance and self-organising communities had arisen in the interstices. However, a simpler explanation might be that to accept the idea of hunter-gatherer egalitarian origins runs counter to his deeper political instincts as an anarchist. If egalitarianism is only to be found among immediate return hunter-gatherer peoples, then that might suggest (as many right-wing critics argue) that it is only possible for it to exist in societies organised into small bands and with little property. That in turn implies that it would be impossible to reproduce in more populous societies with large-scale social production. There is no evidence for this claim, but neither is it the real issue. The undeniable fact that egalitarian and hyper-egalitarian hunter-gatherers do and have existed has never been proof positive that a future society of free association and free access is possible. Our knowledge of egalitarian hunter-gatherers has a different value. It reveals to us the material circumstances under which an egalitarian society can function, and this is not an insight to be tossed aside in favour of a rather weak and unproductive theory.

Material circumstances

What egalitarian hunter-gatherer societies show us is that in order for a dominance hierarchy to arise two conditions must be met. The first is that one section of a population must gain a material advantage of some kind over the rest. This could be something as simple as having access to weapons or other means of coercion. The second is that alternative means of satisfying needs must be unavailable. The disadvantaged population then has no choice but to accept the domina-tion of others. Together, these two conditions allow a dominant group or class to stand between the rest of the population and the satisfaction of their needs.

This situation was neatly illustrated in the 1820s by the fate of the unfortunate Thomas Peel, a cousin of the soon-to-be Prime Minister, Robert Peel. As leader of a syndicate of financiers, Tho-mas proposed to develop a colony at Swan River in western Australia (now the city of Perth). Set-ting out in 1829 from England he took with him provisions, seeds, implements and other means of production to the tune of £50,000, a huge sum at that time. He also took with him 300 men women and children whom he intended to employ in the 250,000 acre colony. Once he arrived in Australia, however, Peel discovered that with land and opportunities available, employment seemed less than desirable to his 300 workers and they rapidly decamped to purse independent lives elsewhere in the colony. As a proponent of colonisation dourly observed, ‘Mr Peel was left without a servant to make his bed or fetch him water from the river.’

As Thomas Peel’s workers demonstrated, we will often resist the domination of capitalist employ-ment if an escape route is available to us. Hunter-gatherers tend to fiercely resist employment when colonial or post-colonial governments try to impose it on them. Workers too in early capital-ist societies demonstrated the same reluctance to accept wage relations. Thanks to a flourishing working-class press in the eastern states of America during the ‘Golden Age’ of capitalism, we know how strongly workers resisted capitalist employment and how humiliated and defeated they felt when it was eventually forced upon them.

Capitalism is a clear example of a dominance hierarchy. Ownership and control of the means of production by the capitalist class is backed up by the coercive force of the state. Historically the elimination of forms of subsistence other than employment was achieved by the enclosure of common lands, thus turning peasants into landless labourers. Material conditions thus gave the capitalist class the ability to stand between the working class and the satisfaction of its needs. With no escape routes available, workers today have no alternative but to accept the domination of capitalist relations. For the majority, employment is the only option. A smaller number become self-employed and escape the domination of a human boss, but are still at the mercy of the capi-talist market. Fewer still attempt to go down the risky and insecure road of starting a business. A few will succeed and end up dominating others, but most will fail, often with dire financial conse-quences to themselves and their families. For the vast majority of us as workers within the capital-ist system there can be no escape from a life of domination and exploitation through capitalist employment. We do, however, have a means of escape from the domination of capitalism itself. And that is not because it is in our human nature to be able freely to choose any social system we like, as G&W would have it, but because material conditions at this time allow us a real and sustainable alternative. As members of the working class, we have the option to act consciously and collectively, to challenge the system, to eliminate class society and put an end to the patterns of domination it inevitably entails. A society of free association and free access is within our grasp – if we choose to reach for it.

HUD

Watch:

- A lecture given by Camilla Power providing an evolutionary perspective on the origins of egalitarianism (bit.ly/3rqCMGX).

- The first of a series of videos critiquing The Dawn of Everything in great detail (bit.ly/3jKKzv2).

- A lecture given by Jerome Lewis on a group of contemporary egalitarian hunter-gatherers in Africa (bit.ly/3rv0z8D).