50 Years in the Party

I first heard about the Socialist Party of Great Britain in 1970 when I was a student in Hull. A couple of fellow students in the house I lived in were always going on about it. Until then I’d followed my parents in being a Labour supporter and saw the nationalisation of industry as the thing to support. But now I was being told that wouldn’t make any difference and I needed to look beyond it to an entirely different kind of society – and on a world scale. This was a society of common ownership and free access to all goods and services. No money, no buying and selling, no market – just production and distribution according to need. No leaders, no national frontiers, just one world – and this was to be achieved by majority democratic political action. This, I was told, if looked at closely, was what Marx had originally advocated and what socialism really meant.

I was incredulous at first and brought out all the arguments I’ve heard countless times since over the years. Human nature, need for gradual reforms, utopianism, over-population, shortage of resources, need for leaders, etc., etc. And I argued for a long time – until I no longer had any more arguments, since they’d all been answered. But I still somehow didn’t want to join a political organisation. I’d never been in one before and it didn’t seem to fit for me. Since no one actually pressed me to join, I just carried on talking and going to the meetings that the SPGB group organised and then helping to sell its journal, the Socialist Standard, in the town centre. But what then finally got me on side was the special edition of the Standard in August 1970. It was called ‘A World of Abundance’ and had articles with titles like ‘The World Can Feed Us All’, ‘Capitalism – Waste – Want’, ‘Not Too Many People’, ‘World Administration’ and a particular compelling one by Ron Cook with the self-explanatory title ‘Progress Perverted: the Technology of Abundance’. With all this it had to happen sooner or later and so, 50 years ago this month, I filled in the membership questionnaire and joined.

In the year that followed I attended meetings in Manchester, where I came from, in Sheffield and in London where, in 1971, the Party held its 66th annual conference. I found tremendous enthusiasm among members, tremendous knowledge of all things social, political and historical and tremendous optimism that the ideas were spreading and the movement growing.

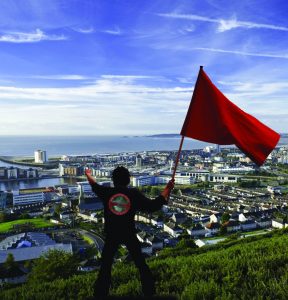

Swansea

When the same year I moved into the world of employment, I found myself in a city, Swansea, with a long-standing branch of the Party, I found myself attending meetings regularly, selling Party literature on the steps of the town’s Central Library, helping to organise public meetings and going to other parties’ and organisations’ meetings to put our case there. A lot was going on at the time. It was the heyday of CND, Anti-Apartheid and Friends of the Earth as well as of those small left-wing political organisations that called themselves ‘socialist’ (IS, IMG, SLL, etc.) but, as far as we were concerned and despite their ‘revolutionary’ rhetoric , at the end of the day were (and still are) just going for reforms of the system and so were just part of the capitalist furniture. I was the branch’s ‘press officer’ and often wrote to the South Wales Evening Post putting these points as well as other aspects of our case. Many of the letters I sent were published. I found all this activity educational and exhilarating and soon found I was able to give talks and engage in public debate myself.

In the late 70s and 80s Swansea Branch built a core of active members across the age range and organised regular meetings that we advertised in the local press. There were topics as diverse as ‘Marxism and Science’, ‘Thatcher and Freedom’, ‘Women are Workers too’, ‘Animal Rights’ ‘Youth and Unemployment’, ‘How Politicians Con You’, ‘Feed the World’, ‘Energy for the Future’, ‘Soap Operas and Socialism’, and ‘John Lennon’. We got good attendances too, and as a key part of our activity sold the Socialist Standard in the city’s shopping precinct and set up an outdoor platform where I was one of our speakers. I would shout myself hoarse on a Saturday morning and got a surprisingly small amount of heckling. I was also writing regularly for the Socialist Standard. We had record Saturday morning sales with an edition of the journal with the words ‘Sex, Sin and Socialism’ emblazoned across the cover. It contained an article written by me on the recently published and much talked about book by anarchist Alex Comfort entitled The Joy of Sex.

We were hawking our literature on the same pedestrian stretch as Ian Bone, a self-avowed anarchist who was later to set up an organisation called Class War. Unlike most of the others there, he really did seem to want a different system of society even if he didn’t quite know what that system was to be and thought the best way to get it was by smashing things. The People newspaper later called him ‘the most dangerous man in Britain’, in which he took great pride. And, perhaps extraordinarily, when some 30 years later he wrote a book about his experiences in Swansea and elsewhere called Bash the Rich, I found myself debating with him at a packed meeting at the Party’s Head Office on Clapham High St with the subject ‘Which Way the Revolution?’. He was still the ‘one-off’ he’d ever been, but we did manage to agree on quite a few things regarding the revolution, even if we remained apart on others, for example violence and the number of classes in capitalist society.

Then there were the ‘speaking tours’ when I gave talks at various branches of the Party as far apart as Bristol, Bournemouth, Cornwall, Bolton, Canterbury and Guildford, some well attended, some pretty sparse. A ‘highlight’ for me was the debate with right-wing guru, Roger Scruton, organised by the Party’s Guildford branch. At the time Scruton, who remained a well-known public figure right up until his death earlier this year, wrote a weekly column in the Times and had raised debate with his book The Meaning of Conservatism. When we met in a pub before the meeting, I found him modest and affable. But he hadn’t bothered to find out what we were about and he asked me to tell him. He seemed to get the hang of it but then in the debate kept forgetting and referring to what had happened in Russia.

Another outstanding moment was a debate in Bolton Town Hall with local MP Tom Sackville, organised by the Bolton branch of the Party and chaired by a local cleric. It was a packed meeting and I managed to put our ‘version’ of socialism on the agenda immediately, after which the MP to his credit didn’t attempt to tar us with the Soviet brush.

I was also, together with a fellow member Pat Wilson, able to arrange a Q and A session for the Socialist Standard with a then leading figure of the burgeoning Green movement, Jonathan Porritt. It was a friendly occasion with Porritt strangely seeming to agree with most of what we said about the need for socialism.

The culmination of all this activity for me was the local election campaigns Swansea Branch ran in the late 1980s when, with the assistance of members from other branches, we knocked on every door in the local ward – twice. Even though we found a surprising amount of agreement on the doorstep, that didn’t really translate into votes, with 92 the maximum number we got in one of the three elections we ran in. An internal Party issue at the time was whether our candidate’s picture should appear on one of our election manifestos. The Party has always eschewed personalities as part of its antipathy to the idea of leaders and so a heated debate took place at the Executive Committee table about whether the candidate, myself, should show his ‘human face’. In the end the picture did appear, as it also did in the local press.

Trade union activity

The 1990s were a bit of an anti-climax in Party activity. The main thing was that the Socialist Standard kept being published and the case it propagated kept being put to readers. This was a period when I started to involve myself in trade union activity in my place of work. It was something I found extremely satisfying – and still do. That’s because you often saw quick results in terms of helping to resolve people’s problems at work, both individually and collectively, and felt you were making some kind of immediate difference, however small. For me it complemented the longer-term project of spreading socialist ideas in society at large and fitted well with the Party’s view of trade unionism as a necessary form of resistance to the tendency of capitalism to take for itself an increasingly large share of the surplus value produced by workers. It also made me fully conscious, if I was not already, of the need for trade unions to be fully independent of political parties and groups and not to succumb to the will of the union’s ‘politicos’ from the left-wing largely Trotskyist groups who were small in number but could still dominate union decision-making and use their position not for the benefit of members but to promote their own political ends. They would (and still do) constantly seek to bounce members into industrial action, even when such action is more likely to be damaging than successful.

Anti-capitalism

In the first decade of this century, as the Party celebrated its 100th anniversary, capitalism found itself facing the twin crises of terrorism and recession. The recession in particular gave rise to a phenomenon I found first surprising and encouraging but then disappointing, that is the quick spread in use of the term ‘capitalism’ with widespread discussion about it in books, magazines and the media. The Party had always freely used the term and, at a personal level, this made me feel a bit uneasy. I wondered whether people would know what we were talking about or would maybe just regard us as cranks or supporters of Russia. Now it was (and still is) everywhere. However, the trouble was, while often calling themselves ‘anti-capitalist’, critics of the system tended to propose more ‘benign’ models of capitalism via reforms seeking to achieve less poverty (e.g. universal basic income) and less waste of resources (e.g. the ‘green’ agenda) without taking into account the fact that reforms, even if alleviating things a little for some, can do nothing to change the basic profit-seeking nature of the system and the inevitable antagonism between what Marx called wage labour and capital.

While the last decade too has been full of proposals for coping with the problems of capitalism within its existing framework, disappointingly it has not seen an obvious rise in consciousness among wage and salary earners of the need for an entirely different kind of society. This is an idea that the Party and the World Socialist Movement have continued to keep alive by publishing literature, holding meetings and seeking to spread the idea in all other ways possible. For example, via our website and, in these pandemic days, the Party’s virtual ‘Discord’ platform.

Looking back over my 50 years in the Party, though a lot has happened, a lot has also remained the same. Capitalism has gone on its merry way with its wars, poverty, unemployment, glaring inequality, environmental degradation, and now a global pandemic. Many campaigns to try and improve it have come – CND, Shelter, Greenpeace, Right to Work, Anti-Nazi League, Child Poverty Action, Occupy, Extinction Rebellion, just to mention a few – and many have gone. But to be fair there have been some changes for the better – racism and sexism for example are definitely on the back foot in many parts of the world, and a whole slew of recent books on human nature have shifted opinion away from the long-held notion that human beings are selfish and competitive creatures rather than naturally cooperative ones.

Looking back over my 50 years in the Party, though a lot has happened, a lot has also remained the same. Capitalism has gone on its merry way with its wars, poverty, unemployment, glaring inequality, environmental degradation, and now a global pandemic. Many campaigns to try and improve it have come – CND, Shelter, Greenpeace, Right to Work, Anti-Nazi League, Child Poverty Action, Occupy, Extinction Rebellion, just to mention a few – and many have gone. But to be fair there have been some changes for the better – racism and sexism for example are definitely on the back foot in many parts of the world, and a whole slew of recent books on human nature have shifted opinion away from the long-held notion that human beings are selfish and competitive creatures rather than naturally cooperative ones.

In addition there is widespread consciousness of the environmental destruction which Rachel Carson pointed to in 1962 but which I only found out about the year I joined. At the same time the ‘experts’ who two years after this published The Limits of Growth, predicting ecological breakdown by the end of the century and calling for population control, were proved wrong. The profit system has of course gone on despoiling the planet but at the same time managing to adapt sufficiently not to cause an environmental apocalypse. It has also given better living standards to many wage and salary workers, while however heaping misery of varying degrees on many others. And it has made a very small number of individuals massively and increasingly wealthy, with the richest 1 percent of the world’s population owning 29 times more than the poorest 20 percent. All of which will continue as long as the capitalist mode of production continues and as long as those with good intentions (and there are many) say they support our aims but somehow think capitalism can gradually be reformed into something better or even into socialism.

I’m not planning to stop any time soon. I’ll carry on helping to keep alive the idea of a society I first heard about more than fifty years ago, since nothing I’ve heard in all that time from either supporters or critics of the present system has discouraged me from seeing the World Socialist Movement’s concept of socialism as the most desirable and most feasible next stage in human social development.

HOWARD MOSS

8 Replies to “50 Years in the Party”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thanks for your commentary Howard. Your account is parallel to my 53 years in the SLPUSA. I’ve always been curious about the SPGB’s lack of articulating the necessary path to a socialist society. How does the SPGB propose getting there? (meaning a socialist society) Without an organized working class aiming to take, hold and maintain production. How does the SPGB outline the process? I understand the political steps, (elect socialists to capitalist political offices for the purpose of preventing the armed state from opposing the working class (doing what?) Tell me about this “administration of things’ Marx vaguely alluded to? How is that constituted? How is that going to work? Surely, the SPGB, having been agitating for over a century must have some rudimentary vision. Certainly you don’t think of socialism by divine intervention. How is it to be accomplished?

Stumped? Working class unity is fundamental to a revolutionary upheaval of capitalism. Right? How is this to be achieved? Agitation for socialism you say? Fine, but what about Unity? How can unity be achieved? Through support of the political party of the working class – a party that demands the replacement of the political state by an “administration of things” – right? How is this administration to be organized and set up? Well, let’s think about that afterwards risking the chaos that would ensue with the destruction of the political state.

Oh, but you protest that there would be no chaos because…? As socialists we know what powered the bourgeois’s overthrow of feudalism. It was the discipline imparted by the ownership of productive property primarily in manufacturing, banking, etc. This would suggest that their is a discipline behind every classes interests – but the working class has no interests except the will to unity and we know that such unity is ephemeral – related to the stomach. So how is the unity to be acquired? Is it not through unionism for the party does not propose to run and maintain the wheels of industry. Is it not through those who know how to make the things society needs for its sustenance? O.K. the SPGB long ago rejected De Leon’s concept of SIU right? So how do you propose to set this “administration of things” in motion?

[From the author of the article (who is not on this forum)]

Bernard, thanks for your comments but they don’t seem to relate directly to the article but seem rather to be about the precise mechanism whereby socialism will come about and then how it will be maintained. But okay, it’s a fair question, even if one that’s been raised and answered many times in the 100-odd years of the Party’s existence.

First of all, in suggesting that working class unity is only based on the ‘stomach’, you seem to be espousing, in part at least, the human nature argument that is often advanced against the idea of a common ownership society, i.e. that people will not cooperate to bring it about or run it because human beings are basically selfish and self-interested and will not engage in social co-operation (or at least, in your view apparently, once they’re fed). If that were true, then it would indeed be an obstacle to a co-operatively run society without money or wages. But it isn’t an argument we would accept or that there’s evidence for. In fact, apart from the case we’ve been making on this for over a century, a whole slew of recent books suggests just the opposite, i.e. that human beings like cooperation on every level and, if they can, prefer to operate as a ‘team’ than as isolated individuals.

With regard to the ‘transition’ to socialism, you seem to be imputing to me arguments I haven’t made. So no ‘rudimentary vision’, no ‘divine intervention’, rather a majority equipped with socialist knowledge and consciousness taking over political power once they’ve worked out a practical plan for how the society they establish will be run (‘administered’ if you like), both in social terms and in terms of production and distribution. Impossible to lay down a ‘path’ to get there in detailed terms (you must know that), except that forces within the current system (including the WSM and any similar movements) lead people towards socialism as the only solution to the never-ending problems thrown up by capitalism.

Thank you for the response and sorry to have broached this subject in a letter of one of your members. You noted “First of all, in suggesting that working class unity is only based on the ‘stomach’, you seem to be espousing…”, was not a suggestion, a recommendation for class unity or anything of the sort. It was meant as a parody of the SPGB position. It is a criticism for lack of a program, guidance, or whatever you want to call it. I made a point that I believe previous revolutionary classes had what one might call a “discipline” imparted to their class with common interests. In the case of the bourgeois overthrow of feudalism it was the powerful impetus of the ownership of capitalist property that unified the class no matter what they may have thought personally of one another. It unified the capitalist class against the monarchy and the feudal lords. In contrast our current propertyless working class has only the will to unity, and that will (if you will) is compromised by hunger. The truism of this fact has been demonstrated time and again and needs no elaborate referencing by the collapse of numerous strike efforts. (There is an excellent film you may have run across called “The Organizer” – on YouTube – that drives home the point). The SPGB is critical of the SLP’s concept of the SIU. Fine! How might the critical process of working class emancipation unfold?

Lacking a response I can only conclude that the SPGB has an overweening aversion to suggesting how the working class might emancipate itself perhaps in fear that it might look like a “plan” beyond the political control of the state. But the fact remains that our class places its collective hands on the means of production hourly, daily, weekly, monthly and yearly. Might that not suggest something or does Marx’s comment that the emancipation of the working class must be an act by the working class itself offer some clue?

Apologies for the late reply. Please allow patience to prevail. One never knows other people’s circumstances. Anyway thanks for your well made points. As you must know the Party fully supports strike action by workers and if that took place under the aegis of a single overarching union that would be fine – and maybe more effective than at present. Indeed strike action might be one of the weapons used by a working class with majority socialist consciousness in order to get more out of the capitalist system prior to making sure that plans are in place before socialism is voted in (nothing wrong with ‘plans’ by the way). I say ‘might’, because it is hypothesis – it has to be. We just don’t know and it would be rash and potentially misleading for us to say otherwise. Having said that, I can only repeat that it isn’t by strike action as such that working class consciousness will be raised to the appropriate level. It should be clear that it’s the conditions of capitalism itself and the developments that brings about which will bring workers to see socialism as a viable alternative. What we can do to assist that it to continue to place the socialist idea in front of workers to the best of our ability so that, when they want an alternative society, they have the free access system we advocate in front of them.

But we do and always have said that the working class should organise to keep production going during and immediately after the socialist revolution.

Our position is that we insist on the necessity and primacy of them first winning control of political power (which presupposes majority agreement with and understanding of socialism) as this is what currently upholds their the capitalist class’s ownership of the means of life. This done , then workers can put into practice their previously worked out plan how to keep production going. We leave it up to the socialist-minded workers at the time to decide in the best way to organise themselves to do this.

Don’t worry, they will do this even if we can’t predict and shouldn’t try to dictate what this should be.

Thanks for your answers. I’ll think about them.