Labour under illusions

Herbert Morrison once said that “Socialism is what the Labour Party does while in office”. On the basis of such a definition, it is little wonder that after six doses of Labour’s ’socialism’, very many workers are anti-’socialist’. At its conference this month, the Labour Party busily invents new ways of enticing voters back to the faith which gave them the massive majority of 1945; that was when they had workers believing in the creation of a Brave New World.

Labour Party conferences are traditional affairs: the delegates call for radical change, the leaders politely humour them. When in office, there is talk of betrayal by the right wing leaders; when in opposition. Labour’s record is recalled with glory and all social evils are attributed to the malice of the Tories. The naive radicals who still believe in Clause Four remind their comrades of the dangers of diversion, while many of their time serving comrades, grown fat from the trust of the ignorant, go through the ritual motions and look forward to the diversions of power. If the Labour Party is a church, it is one in which the rich and powerful leaders occupy the pulpit, the rank and file kneel down with their eyes closed, and the trade unions contribute generously to the collections.

Despite the failure of the six Labour governments to enact fundamental social change, there will inevitably be some Labourites who will plead with the conference that what is required is a radical economic programme. The left of the Labour Party maintain that their policies could tackle the problems facing the working class in Britain. Their economic programme rests upon three principles: that wealth can be redistributed so as to extensively erode, if not eradicate, social inequality; that state intervention — or even total control — in the economy would take power away from the capitalist minority and give it to the public; that social democracy (parliamentary reformism) will eventually break down the unequal structure of British society. The proponents of these principles argue that no Labour government has yet seriously applied them, but that if this happened the position of ‘the ordinary people’ — a term which the Labour Party uses to describe its followers (perhaps not unrelated to the level of their awareness) — would be remarkably improved. The debate between the left and right is essentially about how much emphasis to give to these three principles.

The problem with both sides of Labour’s economic debate is that they fail to locate the root of economic inequality. They are dealing with the symptoms rather than the cause, and so end up engaging in a futile effort to make the system run fairly; in fact it is running fairly insofar as it is a system which operates in the interests of those who own and control vast amounts of property.

The existence of the capitalist system is totally ignored by Labour economists. Failure to recognise capitalism leads to the ahistorical belief that the features of social organisation existing now can never be fundamentally altered. What are the features which constitute a capitalist system? Private ownership of the means of wealth production and distribution by members of a minority class; a condition of wage slavery for the majority of the population who must sell their labour power in order to live; production for the market with a view to profit; national boundaries, competition and war; the existence of a coercive state to defend private property. Wherever these features exist there is capitalism. Two questions must be answered. Does the economic programme of the Labour Party in any way affect the misery and inequality which are a consequence of capitalism? If not, what can? We can answer the first question by considering the three tenets of Labour’s economic objective.

1. The redistribution of wealth

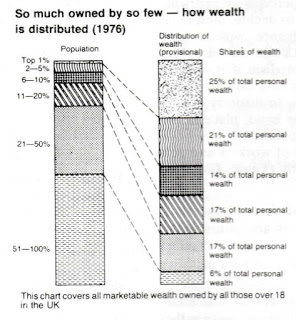

It is claimed that we live in a property-owning democracy. The following table, indicating the ownership of marketable wealth in terms of proportion of the population, shows the markedly undemocratic nature of wealth division under capitalism (see graph).

The line taken by the Labour Party is quite simple: wealth is unequally divided; what we must do is divide it up equally. Graduated income tax, subsidies to certain industries, and attempts to close the rift between high and low paid workers, have been the means the left has urged Labour governments to adopt. But these policies have failed: although there has been an apparent diffusion of wealth since the beginning of the century, the process has been one of redistribution within the capitalist class and within the working class. As Westergaard and Resler point out, the reason for the transfer of wealth ownership within the ruling class

. . . from the richest one per cent to those a little way down the scale from them is plain. The shift represents, primarily or even exclusively, the measures taken by the very rich to safeguard their wealth against taxation. Property which is transferred to relatives, or others, some time before the death of the original owner has not been liable to death duty. Protection of private wealth has therefore required — and produced — earlier divisions of large holdings of wealth among kinsfolk, with little effect on the social distribution of capital. (Class in a Capitalist Society)

Thus the redistribution of wealth at the top, which is the only significant redistribution to have taken place this century, has been a means of preserving rather than spreading the privilege of ownership. Indeed, the recently published report of the Royal Commission on the Distribution of Wealth and Income has shown that the top one percent actually owned a more concentrated section of accumulated wealth during the first three years of the last Labour government than they had done under Heath’s Tory government.

As for the working class, their economic position has remained unaltered after six Labour governments. Although pay has increased and conditions are apparently better (although worse relative to the increased productivity of the working class over the last eighty years), workers have nothing for which to thank the Macdonalds, the Attlees, the Wilsons and the Callaghans. Workers still produce all the wealth of society in return for a wage or salary. Wages, being the price of labour power, rise and fall in rough correlation with other commodity prices.

Labour has failed to solve the problems which arise from the fact that approximately ninety per cent of the British population own ten per cent of the wealth. By choosing an arbitrarily determined line of poverty, Labour has attempted (unsuccessfully) to deal with the excesses of deprivation without facing the basic problem, which is the deprivation of the vast majority of the full fruits of their labour. The programme to reduce poverty is simply a redistribution of poverty within the working class. The Labour Party wants to make distribution ‘fair’, while leaving the means of wealth production in the hands of a minority. Westergaard and Resler (whose book is to be highly recommended to readers seeking statistical information concerning the power structure in contemporary capitalism) are forced to conclude that despite claims that Labour would fundamentally redistribute wealth:

Private capital is massively concentrated in the hands of a small minority, though it is now more widely dispersed within the families of the wealthy than in the past, as a protection against taxation. Some one per cent of the adult population have as large a share of wealth as the poorest thirty per cent or so. Two-fifths or more of their income comes from investments; a matter of little surprise, since they alone own about thirty per cent of all private wealth, and four-fifths of all company stock in personal hands. Private property, individual or corporate, is the pivot of a capitalist economy, as much in its ‘welfare’ form as before. It is for that reason above all that, despite its expansion of production, capitalism can make no claim to a steadily more equal spread of wealth. Inequality is entrenched in its institutional structure.

2. Nationalisation and state subsidies

The argument for widespread nationalisation of industry which is frequently advanced by groups on the left of the Labour Party goes like this: inequality of wealth ownership results in a disparity of living standards; the state is the elected representative of the people; by nationalising industry, the people, through the state machine, would have control over industry; the result would be that the people in general, through their elected Members of Parliament, would control the economy. To thousands of radical labourites and trade unionists, the logic of this series of propositions seems compelling.

In fact, the argument rests upon several fallacious assumptions. The most serious is to imagine that the state represents the people who elect a government. This is entirely to disregard the existence of social class. Under capitalism, the state acts as the regulator of affairs for the capitalist class. The police, the army, the prisons, the courts, the schools, are paid for by the state, by the capitalists acting in their collective interest. State subsidies or ownership of industry have usually been imposed because private capitalists have called upon the rest of their class to collectively invest in a section of the economy. But it should be remembered that capitalists do not invest to provide services, employment or social harmony.

This leads to the second fallacy in the nationalisation argument. It is assumed that the state is able to be less concerned about profits than would a board of directors. In fact, all Nationalisation Acts contain clauses saying that profits must be made. And where there are profits there is exploitation. Whether workers are exploited by the state or by private capitalists makes little difference: wage labour equals exploitation for profit.

Thirdly, it is false to suggest that nationalisation dispossesses capitalists of power over the economy. All nationalisation has been based upon ‘fair compensation’ for the previous owners. Instead of depending upon the variations of share returns, the capitalist whose firm has been nationalised can rely upon the regular interest of state bonds for the rest of his parasitic life. Neither does nationalisation take away the capitalists’ control over industry. The boards of the nationalised industries are still dominated by members of the ruling class.

There is something of a myth that Labour is the party of nationalisation and that nationalisation is the central economic aim of socialists. Neither of these assumptions could be further from the truth. In the nineteenth century, both Liberal and Tory governments had a long record of nationalisation. No modem government could survive without intervening in industry, including the provision of subsidies and services. Sir Keith Joseph will learn this lesson, just as Edward Heath did when he subsidised Rolls Royce despite his brave words about not financing ‘lame ducks’. Nationalisation has nothing to do with socialism: it is state capitalism.

A quarter of British workers are employed by the state. Are they better off than workers exploited in the private sector? In Russia and most of Eastern Europe the main sectors of the economy have been nationalised. Does production for human needs prevail in those countries, or is it not the case that profit is the motive for production there as it is in the West? British Rail is nominally publically owned. Ever tried travelling on one of the trains which you nominally possess without buying a ticket? That state control equals public control is a pernicious myth. The Labour Party is guilty of perpetuating it.

3. Social democracy

When Labourites claim to be social democrats it means that they are reformists looking towards Parliament to solve the ills of the capitalist system. The Labour Party’s reformism is an admission that it has failed to eradicate inequality either by redistributing wealth or by state intervention. Labour reforms are simply intended to make the poor less uncomfortable. It should also be borne in mind that welfare reform is neither a particular feature of Labour administrations, nor an act of benevolence by the state. All parties have initiated a certain degree of welfare reform. It is in the interest of the capitalist class to have a moderately healthy, educated, mobile working class. That it might also be in the temporary interest of the workers is no reason for supporting it. Reforms are not given as an act of charity by the ruling class, but are usually paid for by means of a general fall in wages. In short, welfare reforms usually involve a redistribution of wealth from one section of the working class to another.

Reformism marks an acquiescence in the present system of society. And if there is one thing no Labour Party conference will ever do. it is to break away from its reformist origins. The Labour Party may have started out with some ideals, but its history has been one of persistent betrayal of the working class.

Steve Coleman