Within those walls

As we drove along the narrow road bordered by grass with trees and shrubs beyond, I felt curious yet mildly uneasy about our destination. The others were laughing and joking around me, apparently thinking nothing of our impending encounter, though it was true that most of them had been there before. I was struck by the bleak, apparently deserted surroundings, just a stone’s throw from a newly completed section of motorway hidden in a cutting beyond a high wire fence.

As we drove along the narrow road bordered by grass with trees and shrubs beyond, I felt curious yet mildly uneasy about our destination. The others were laughing and joking around me, apparently thinking nothing of our impending encounter, though it was true that most of them had been there before. I was struck by the bleak, apparently deserted surroundings, just a stone’s throw from a newly completed section of motorway hidden in a cutting beyond a high wire fence.

Then suddenly we were upon it: a large group of grey, uninviting buildings linked together by a single interminable corridor. There were annexes and outbuildings which had been added at intervals. Surrounding the entire establishment was a high stone wall, interrupted in places by large cottages. High atop the central administration building was a clock tower but each clock face had stopped on a different time. I had been expecting a more attractive and friendly building nestling in leafy grounds. Instead, the whole place was gravely forebidding, with an aura of despair reminiscent of a prison save for the absence of bars on the windows.

Originally the establishment was a virtually self-contained unit with its own farm, set well away from the town which had grown and crept towards the boundary wall. Despite this, there was still an inescapable remoteness about the place, a sense of having been abandoned and forgotten by society. Our guide led us into the foyer, a cold unsociable room almost noiseless but for distant echoing footsteps and the buzzing of the telephone switchboard behind the reception window. There was a scruffy, middle-aged man on the floor by a wall, head propped up on one arm. voraciously smoking a cigarette held between fingers burned by years of dragging discarded nips down to the filter. His staring eyes seemed menacing but his manner suggested that he had no will to do anything other than lie around smoking second-hand cigarettes.

We filed through a double door into a reverberating corridor with hideous decor punctuated by patches of bare plaster. There were more vacant-looking people wandering aimlessly up and down. Some were recognised by members of my group, who offered greetings. A couple acknowledged the attention; most were silent and unresponsive, as if senseless. I noticed that they were all wearing very similar clothing: the men all in bland shirts with huge collars, check jackets and crimplene trousers and the women in shapeless dresses that made them look like animated curtains.

I hesitantly followed the others into a long high-ceilinged room lined on either side with old tubular-framed beds. Once through the door, my nostrils were assaulted by a pungent offensive odour. The dormitory was stark and soulless, not a homely or personal artefact in sight. The beds were all covered with identical counterpanes, the only means of identification being pieces of card stuck to the ends of the bedsteads on which were written the names of the night-time occupants.

We were standing on a hideously patterned carpet which led like a causeway over the slippery linoleum to another door, also with two handles. Through the glass I could make out several haggard figures moving to and fro. They looked as if they were anxiously awaiting the arrival of something. We entered this living area, which had thoughtfully been labelled above the door with a large placard. It later occurred to me that to describe it as a “living” room was something of a misrepresentation; “existing” room would have been a far more accurate description. I was unprepared for the scene which confronted me.

The impatient men wandered about, apparently oblivious of our presence. Nearby there were many languid figures seated in uncomfortable plastic-covered armchairs, some half asleep, others staring into the room or fiddling with their clothing. Apart from one man periodically growling at the odorous atmosphere, the only sound was that emanating from a television set placed high on one wall.

Next we called on some younger women, trooping up two flights of worn steps like class and teacher on an outing to the local museum. The place was markedly different; it had a more homely atmosphere. The sleeping arrangements were also remarkable because the beds were in the same huge room as the living area but enclosed in four glass-topped cubicles. I noticed a woman peering at us from within one of these cubicles; her eyes were petrified into an iron stare, isolated inside dark rings. She looked as if she hadn’t slept for weeks.

We followed our guide back down the stairs to the endless corridor, talking earnestly about what we had seen. After another brisk trek we were led through a door into the warm June sunshine — bright, refreshing and gratifying. We walked up a concrete path towards a prefabricated building near the boundary wall.

Inside there were three tables littered with half-finished wicker trays, stools with cord seats and some recently moulded resin figures. At another table there were four men playing a disinterested game of cards. The atmosphere was one of indifference, although a couple of people were making an heroic effort to master those blister-inducing pieces of cane to produce a passable tea tray. Others sat and glared with undisguised contempt at their work through clouds of cigarette smoke.

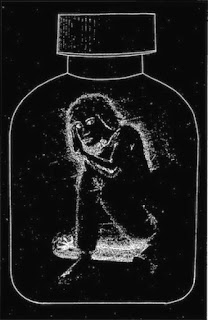

I’ve briefly described my first impressions of a psychiatric hospital, in which I subsequently worked for almost three years. The experience was both enlightening and disturbing. The place was a spectre from the past, one of those places we all know exist but don’t like to acknowledge. Within its antiquated walls, time became inert for most of the inhabitants. There was a different world outside of high speed travel, microchip technology, fast food, piped music and canned laughter. Inside there was safety, comfort and seclusion; security in a persistent and unvarying routine. There was of course a vivid window on the world in the form of the television screen but I discovered later that it was more of an intruder than a welcome guest. Here second-hand, pre-packaged escapism was redundant and there was no place for sophistry. The people here made their own world, away from the tangled. mind-bending turmoil outside, insulated in a cocoon of predictability and convention. There were no decisions to be made, no bills demanding to be paid, no production targets to be met. This place was indeed a sanctuary from the economic and social battlefield outside . . . an asylum.

Although my first impressions were so unpleasant I later developed a fondness for the place and the patients in it, along with a firm contempt for the largely reactionary psychiatrists and their methods of “treatment”. During my short experience it became clear to me that the majority of people admitted to a psychiatric hospital would not be there but for poverty and the stress of modern living. Their treatment could only be a palliative, usually in the form of drugs, to enable them to cope — accept the unacceptable, to render them docile and controllable. But the causes of their illnesses would still be there when they returned home, and it was the real causes that were rarely addressed.

Nick Bunskill