Harold Macmillan, who was also known as Supermac, or the Great Unflappable, or Lord Stockton, was said to be a complex character. Nothing is more beloved of political biographers; the simple characters, like the workers who allow themselves to be dazzled by a politician’s reputation, never become famous, in life or death. Macmillan’s role — ascribed to him partly by himself and partly by those who observed him — was one which he acted out almost to the end. Near death, he made his frail way to the House of Lords to depict Thatcherite capitalism in a style startling for its audacious affectations. He grabbed the headlines by telling us that the striking miners were the men who had beaten the Kaiser (Macmillan seemed to suffer a recurring difficulty in separating workers on the picket lines from those in the First World War trenches. He once negotiated his way out of a rail strike with tearful reminiscences of Passchendaele. Were the union leaders really simple enough to be impressed by such outrageous waffle?) At the time of that speech, the miners were engaged in a bitter struggle, not against some foreign power but in an effort to fend off the policies of the British ruling class. They were not able to do to

Ian MacGregor what Macmillan thought they had done to the Kaiser. Another of his famous recent statements was his protest that the Tory plans to privatise nationalised industries amounted to selling off the family silver (of course, as a Conservative himself Macmillan should have been opposed to nationalisation in the first place) Workers who don’t have any silver in the family, who perhaps rely for their houseware on collecting enough tokens at petrol stations, might have wondered what it matters if the industries where they work — where they are exploited — change hands.

Of course Macmillan’s cosy and reassuring style did not match with reality. The England he casually depicted did not exist and never has existed. There was never a time when the two classes of capitalism amicably co-operated to guard a joint interest. There never was — never could be a joint interest, although it suits the purpose of people like Macmillan to pretend that there is. The two classes have always been, and must always be. in opposition to each other. Politicians try to hide the fact —

Tebbit does it by prompting us to buy shares in state industries. Wilson did it through enthusiastic visions of capitalist prosperity through automated industry. Macmillan did it by treating us like the cared-for tenants of some benign country squire. However they try it, it amounts to the same thing — an attempt to deceive us into supporting a social system which by any humane or reasonable standards is unsupportable.

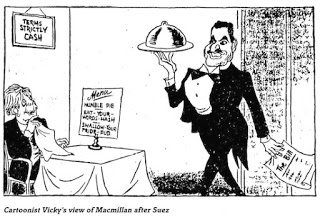

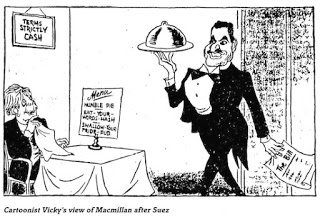

Macmillan replaced

Anthony Eden as Prime Minister in February 1957, after the debacle of the Suez invasion, which is not one of the Tories’ proudest memories. The nationalisation of the Suez Canal, by the Egyptian government under Nasser, was one of a series of steps in the decline of British power and influence in the Middle East. For Eden it was a sticking point; according to recently released Cabinet papers he was determined to use force (by which he meant ordering British workers to fight and die there) to overthrow Nasser and as the crisis developed, and with it Eden’s painful and exhausting illness, the matter became a feverish obsession with him. The more hysterical newspapers wallowed in it; for them it was another case of Good (Eden) standing up to Evil (Nasser). The Egyptian government. led by a greedy maniac, were devious, grasping and untrustworthy while the British, led by an elegant Old Etonian, were frank, generous and utterly honourable.

It is no unusual thing for hysterical patriotism to swamp the truth, which in this case was that whole episode was based on a secret conspiracy between the British, French and Israeli governments. Eden sent his Foreign Secretary uncomplaining, pliable

Selwyn Lloyd to France to work out a deal under which the Israelis would attack Egypt and so give the British and French a pretext for intervention on the grounds that they were defending the Canal as an international waterway. At the time, these honourable gentlemen of England denied that there was any conspiracy, or even collusion; they lied to the House of Commons and, according to the

Guardian of 30 October 1986, Eden personally saw to it that the English version of the agreement which Selwyn Lloyd brought back was destroyed. But the facts were never in doubt. Some prominent Tories, like Minister of Defence Walter Monckton, made their opposition plain while others, like

R. A. Butler, did so more discreetly. Macmillan was one of the hawks; perhaps he saw his chance for the future. He favoured, not just occupying the Canal but “. . . to seek out and destroy Nasser’s armies and overthrow his government” (

The Times 1 January 1987) which, he argued, would deal with “. . . the whole problem of pacification (sic) of the Middle East” (Macmillan,

Riding The Storm).

It was that stand, more than anything, which ensured Macmillan’s succession of Eden, for it offered the beleaguered Tories the hope that the distress and embarrassment of Suez would be wiped away and, perhaps, a new age of glorious British imperialism ushered in. Of Butler, the only other serious contender:

There is no doubt that his attitude over Suez depreciated Butler’s standing both in the Cabinet and in the Parliamentary Party. This was particularly true of the so-called Suez group, who criticised his assumed opposition to the military intervention in Egypt and his reputedly lukewarm support of action after it had been taken. (Nigel Fisher, The Tory Leaders).

In fact. Macmillan’s support for the war was anything but consistent. At first he vowed that as Chancellor of the Exchequer he was prepared to pawn every picture in the National Gallery to pay for it but when the financial stress of the invasion became plain he abruptly changed his attitude and threatened to resign if there was not an immediate cease-fire. Macmillan himself described the affair in less than candid terms:

It has been stated that as Chancellor of the Exchequer I made an urgent plea that we should submit to circumstances and acknowledge our virtual defeat. I have often been reproached for having been at the same time one of the most keen supporters of strong action in the Middle East and one of the most rapid to withdraw when that policy met a serious check. “First in. first out” was to be the elegant expression of one of my chief Labour critics on many subsequent occasions. (Riding The Storm).

But of this shrewd, cynical manipulation the Tories remembered only as much as they found comforting. Macmillan had done enough to convince them that he was the leader to unite them and to revive the imperialist traditions of British capitalism. He was, after all, another Old Etonian, he had been to one of the smarter Oxford colleges and an officer in the Guards. “An overwhelming majority of Cabinet Ministers was in favour of Macmillan as Eden’s successor, and back-bench opinion . . . strongly endorsed this view” (

Lord Kilmuir, the Lord Chancellor,

Political Adventure).

These hopes were soon disappointed, as Macmillan presided over the dismantling of much of what remained of the old British Empire. In Africa and the Middle East, in one state after another, the British ruling class had waged a long campaign against nationalist guerillas. They might have carried on in this way for a very long time — indeed one Colonial Secretary was stupid enough to declare that Cyprus, where one of the bitterest campaigns was being fought, would “never” throw off British rule. Macmillan had to face the reality that in the post-1945 world British capitalism could not undertake another Boer War. In addition the American capitalist class had long been working to end the system of Commonwealth Preference, which obstructed their access to valuable markets and sources of raw materials. When the British government signalled their defeat in Cyprus by allowing the exiled leader Makarios to return from exile, the Tories’ arch imperialist, Lord Salisbury, had come to his sticking point and he resigned in protest. Macmillan seemed unperturbed: “. . . he had chosen an issue on which no strong public opinion would be aroused . . .” The Tories were bewildered that this man of such impeccable background should behave like any other politician, with actions which contradicted what he allowed them to think of as his principles.

It was his nonchalance in such situations which gave Macmillan the reputation for being unflappable; “father of the nation” he was called by David Steel when he died. Perhaps his most audacious claim, in 1957, was that “. . . most of our people have never had it so good,” — were living in “. . . a state of prosperity such as we have never had in my lifetime nor indeed ever in the history of this country”. At the time many workers had not adjusted to the wider ownership of cars, to watching television and using appliances like washing machines. Viewed through a car windscreen, capitalism to them had changed its nature to a sort of hire purchase debt which stretched into infinity. A simpler and more useful analysis of that time was that capitalism was in boom, not just in Britain but throughout the world. At such times workers are liable to look back on the slumps of the past and draw the wrong conclusion — that they are living at a time when many of capitalisms basic problems have been solved.

In fact, Macmillan’s speech was a warning of possible recession to come and when it did come, in the early 1960s, and his government ran into a trough of unpopularity, his nonchalance deserted him. The hysteria which demanded a fight to the finish with Nasser was turned onto his own Cabinet and in July 1962 he sacked a third of them including his Chancellor of the Exchequer Selwyn Lloyd (“so good and so loyal” Macmillan had written of Lloyd in 1958) who. as might be expected of one who would obviously do anything for British capitalism, went quietly and loyally. Macmillan’s last mistake as Premier was to support Alec Douglas-Home as his successor, which helped the Labour Party’s propaganda that, at a time when British capitalism needed to join the white-hot technological age, the Tories remained steeped in aristocratic complacency. One way and another, Macmillan must have driven numbers of people into support of the Labour Party and so helped Wilson’s victories in 1964 and 1966. One of the last of his many insults to the working class was the choice of Stockton as his title when he went to the House of Lords for this town, noted for its chronic, grinding poverty, could not happily be linked with a capitalist in affluent retirement in a huge stately home in Sussex.

Macmillan’s exterior was that of the charming, sincere amateur but behind it he was a ruthlessly ambitious politician. His advance to the Premiership was no accident and neither was his languid vision of an England where, as he put it after his 1959 election victory, “the class war is obsolete” — where the grimy, impoverished factory worker cares for the landed aristocrat, and vice versa, because each knows their place. He was said to have been savaged in mind as well as in body by his terrible experiences in the trenches but this did not prevent him supporting other, equally horrifying, wars. His protests against the ghastly suffering in Stockton-on-Tees would have been more impressive had he not been a member of a party standing so blatantly for the social system which produces such problems. One of his claims to fame was that, as Minister of Housing after the 1951 election, he was responsible for over 300,000 working class homes being built in a year. But in many cases the standards of design and construction were as gimmicky as a Premium Bond. Now, even the planners concede that the estates built at that time were a terrible mistake — for the people who have had to survive in those arrogantly conceived, badly designed, jerry-built deserts, not for the man in his stately home in Sussex who won popularity through them.

How do we assess Macmillan? When he became MP for Stockton unemployment there stood at 29 per cent. In the 1980s, as he approached the end of his life, it stood at 28 per cent. Capitalism has been through its cycles, of boom and slump, war and “peace” and has not changed in any significant way. It is an apt comment on the futility of his life, and on the lives of all the other apologists for capitalism and most of all on the political ignorance of the patient, vulnerable people who keep them in power.

Ivan