Book Review: A Fight to the Finish

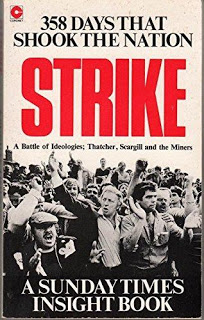

Strike, Sunday Times Insight Team. (Coronet Books £2.50)

Strike, Sunday Times Insight Team. (Coronet Books £2.50)This book is unlikely to find much favour among left wing activists, preoccupied as they are with weaving over the calamitous reality of the coal strike a blanket of myths:

- that it was all caused by the malevolent intent of Thatcher, MacGregor and the rest;

- that Arthur Scargill was a saviour of the working class, crucified by the media;

- that the miners were struggling for “their” jobs and “their” communities:

- that the coal industry can and should be run for the benefit and comfort of the miners under a capitalist society;

- that it can all be put to rights by the election of another Labour government who will release the gaoled miners, repay the fines imposed by the courts, re-employ the sacked strikers, restore the union’s sequestrated funds . . .

The British coal industry, which in its heyday contributed so much to the profits of the capitalist class, has been in continuous decline since the First World War. In 1913 there were 3.000 working pits producing some 300m tonnes a year; when the industry was nationalised in 1947 there were under one thousand turning out 200m tonnes a year. Even so, the industry in 1947 supplied about 90 per cent of the primary energy requirements in Britain. One plan after another — none of them having much basis in reality — promised heavier investment, busier pits, higher production. more secure jobs. At times — for example in the oil crisis of 1973/4 — the optimism was tinged with hysteria. In the event, the plans were undermined by competition from other energy sources, notably oil and natural gas and by 1974 coal was filling barely one third of the total fuel market in Britain. The profitability of individual pits came under the accountants’ scrutiny and many of those which weighed in the wrong side of the balance sheet were closed. This happened under Labour governments as well as under the Tories and when Heath’s 1970 victory threw out the Wilson government there were less than 300 active pits.

To begin with, the closures — in spite of the dramatic changes they wrought, for example in the Rhondda which was left with only one pit — were accomplished with little opposition. British capitalism at large was still booming enough to provide plenty of other jobs to miners who were offered seductive redundancy terms. In general the NUM co-operated quietly under a succession of leaders who liked to think they were craftily applying the politics of the possible. But as the slump deepened the miners’ resistance to redundancy. to uprooting themselves and their families, stiffened. In 1981, by an emphatic majority, they elected as their president, the much loved, much hated Arthur Scargill.

The new NUM President had been prominent in — perhaps largely responsible for — the miners’ victories in 1972 and 1974 and he appeared to be obsessed by, and to have learned nothing from, the experiences. It is difficult to explain his policies and actions other than through a resolve to engage the government in a titanic, no-compromise fight to the finish, at whatever cost. But if the government had been defeated in the 1970s. and had beat an apparently humiliating retreat over closures in 1981, by 1984 they were ready for a war of attrition with whichever trade union was prepared to go over the top. Nicholas Ridley, now Minister for Transport, contributed importantly to the government’s strategy and there could have been few more obvious choices for the new Chairman of the NCB than Ian MacGregor (who had first been approached, as a prospective hatchet man for British Leyland. by a Labour Industry Secretary). MacGregor later described the strike as a poker game, in which the first one to blink was the loser: ‘I don’t intend to blink”.

Thereafter, the government’s tactics could hardly be faulted. Most vitally they kept the power stations supplied with coal by using small, non-union road transport firms and by importing coal through minor ports like Flixborough. Thus an exceptionally severe winter was survived without any power cuts. They hastily appeased other strikes — in the docks and by the pit deputies — which posed a crucial threat to their strategy. Any possible sympathy among other important unions was diverted with a propaganda campaign which emphasised the comparatively large redundancy payments on offer to the miners. They consistently harped on the NUM’s refusal to hold a ballot, which was Scargill’s most damaging mistake. Finally, the whole policy was asserted by a massive, massively organised, police presence which did not baulk at breaking the law in order to frustrate the pickets.

Against that the miners could oppose their courage, their ingenuity, their tradition of militancy — and Scargill’s empty rhetoric. Unity they could not offer, for Scargill’s refusal to hold a ballot had prevented that. As the going got tougher Scargill tried to conceal reality beneath bluster and with claims of an imminent victory, reminiscent of Hitler’s last days in the Berlin bunker. The time came when with each day out the miners’ resolve was bound to weaken. The NCB response to this was to harden its face, refusing Scargill’s desperate appeal to return to a settlement which he had earlier refused. Perhaps the breaking point came at Christmas, when the miners’ poignant celebrations were followed by a sickening sense of anti-climax. There was little else for them to do but surrender. leaving the NUM and the rest of the union movement with little strength to resist the employers’ onslaughts.

This is not to say that all was well on the other side of the barricades, where MacGregor was a disaster in the cynical, slippery game of ruling class propaganda. At times the divisions in the NCB management were almost as marked as those in the NUM. What counted in the end. above the influences of any personalities, were the basic facts that coal is a commodity — produced for sale and profit — and that the endurance of workers on strike is limited by their inability to survive without an income. As happened in 1926. the miners were really starved into submission.

Strike is a compact, informative account of that year of conflict but its sympathies show through. Andrew Neil, editor of the Sunday Times, introduces the book with glowing praise as “. . . impartial and well-informed . . . accurate . .. scoop of the year. . .” while assuring us that the Insight team work independently of the paper’s editorial policy, which is ” . . for the sake of liberal democracy, economic recovery and the rolling back of union power”. Perhaps that is why Strike, so illuminating on some issues, gives so little attention to the savage behaviour of the police and to their other illegal policies, such as the obstruction of public thoroughfares, which have such serious implications for political and trade union activity. It is similarly scant about the stoicism and courage of the miners and their families in sustaining so long and bitter a struggle.

This is not a comfortable book for left wingers because of the lessons which can be drawn from it by the class conscious. Workers have no “right” to their jobs; they are employed only on the prospect that their labour will yield profit to the capitalists. In a class divided society conflict is inevitable but in this the strike should be a weapon of last resort, not the plaything of a leader. Strikes should proceed on a democratic decision and ideally should be brief as well as concentrated. It is vital to separate the struggles on the industrial field, which are about the division of wealth under capitalism, from that on the political field, which is concerned with the revolution to dispossess the capitalists of their monopoly of the means of life. It is on the political field, and not the industrial, that the working class is able to contest with the state, to control it for their own emancipation.

For the workers to ignore these lessons is futile and dangerous. History is a guide for future action and that of the coal strike points unwaveringly to the urgent need for a new social system.