Book Review: A Killing

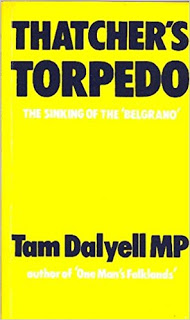

Tam Dalyell. Thatcher’s Torpedo: The Sinking of the ‘Belgrano’ (Cecil Woolf, 1983).

Tam Dalyell. Thatcher’s Torpedo: The Sinking of the ‘Belgrano’ (Cecil Woolf, 1983).

Tam Dalyell’s book is not an analysis of why hostilities arose between the British and the Argentinian governments over the Falklands but an indictment of the strategy adopted by the Thatcher government. According to Paul Rogers in his introduction to the book a harsh campaign of economic sanctions could have been directed against Argentina but the British government “embarked on the killing war within 36 hours of the declaration of US political and economic support”. Dalyell goes on to argue that although there was a possibility of a negotiated peace settlement through the intervention of the Peruvian government, the policy of the British government was in opposition to such a settlement:

The charge laid at the door of the British Prime Minister could hardly be more grave. It is specifically that, along with her Defence Secretary and the Chairman of the Conservative Party, but in the absence of the Foreign Secretary, she coldly and deliberately gave the orders to sink the Belgrano, in the knowledge that an honourable peace was on offer and in the expectation — all too justified — that the Conqueror’s torpedoes would torpedo the peace negotiations.

The reason for this seemingly calculated act of cynicism is seen by Dalyell as a means by which the nation would rally behind Thatcher and in order to secure Thatcher’s continued leadership of the Conservative Party. Dalyell is not opposed to war; he says of the Falklands that “the conditions for a just war were not met”. He does not explain what conditions would give rise to a “just war”, given that he secs the first responsibility of politicians as avoiding war. What he does lament is the consequent cost of undertaking military action over the Falklands:

The £880 million for Stanley airport is only the most dramatic item of expenditure in a horrendous list of costs associated with Fortress Falklands.

One important point that Dalyell does make, but does not develop sufficiently, is his argument that “we live, do we not, in an age of misinformation”. His attempts to uncover the events leading up to the sinking of the Belgrano attest to that fact but more importantly it is the selective use of information that is fed to the working class in order to secure its support that should be considered.

The whole concept of democracy within capitalism comes into question when our view of the world is being dictated by the government in the so-called interests of the nation. The working class do not have the opportunity to negotiate whether they will fight and the Falklands emphasised the manipulation of the working class to gain its support. Dalyell argues that he raises the question of the sinking of the Belgrano because “I believe the good name of Britain has been besmirched”. He should rather lament the spilling of working-class blood, both British and Argentinian, in order to secure economic influence over a group of South Atlantic islands.

Dalyell can lament the lack of parliamentary democracy in being unable to discover the facts behind government strategy but there are larger questions to consider. It is members of the working class who must fight wars on the instruction of their parliamentary leaders but it is the working class who will receive no benefit as a result of those wars.

Philip Bentley