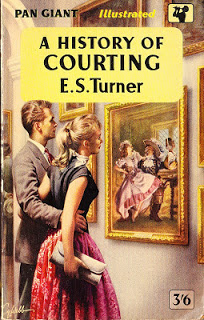

Pan Books have recently republished E. S. Turner’s History of Courting in pocket form at 3s. 6d. Mr. Turner has achieved a considerable reputation for the writing of light, informative books on subjects that lend themselves to a humorous, somewhat ironical approach. This, first published in 1954, is his most recent one; earlier successes were Boys Will be Boys, a study of blood-and-thunder literature, The Shocking History of Advertising and Roads to Ruin.The book succeeds in what appears to be the chief object in all Mr. Turner’s writing—it is highly entertaining. It contains many very funny quotations, the style is without any of the pomposity associated with many books on history, and the points are made very neatly. Many of Mr. Turner’s own comments are shrewd, and he has made a very good selection of other authors’ comments as well.

Pan Books have recently republished E. S. Turner’s History of Courting in pocket form at 3s. 6d. Mr. Turner has achieved a considerable reputation for the writing of light, informative books on subjects that lend themselves to a humorous, somewhat ironical approach. This, first published in 1954, is his most recent one; earlier successes were Boys Will be Boys, a study of blood-and-thunder literature, The Shocking History of Advertising and Roads to Ruin.The book succeeds in what appears to be the chief object in all Mr. Turner’s writing—it is highly entertaining. It contains many very funny quotations, the style is without any of the pomposity associated with many books on history, and the points are made very neatly. Many of Mr. Turner’s own comments are shrewd, and he has made a very good selection of other authors’ comments as well.

There is so much enjoyment to be got from reading this book that any criticism may appear unkind. However, the jokes being told and appreciated, some reflections on the real nature of the subject are not out of place; for though no subject gives rise to so much mirth, perhaps no subject is taken so seriously by so many people. Courting has played an increasingly important part in people’s lives from the 12th century onwards. Any analysis of courting should also be an analysis of the development of society. This is not to suggest that a history of courting should attempt to be a history of social development; but the background should be sketched in and be implicit in what is written.

Mr. Turner does not attempt a comprehensive survey, but this, of course, is not a criticism; what can be said is that the book does not make any important generalizations about the subject. Mr. Turner’s conclusions, where he arrives at any, are somewhat commonplace. There is a continual shifting of the survey in time and place in order to take in those countries and times providing the most entertaining material.

One important point seems to have escaped him completely. The history of courting is not simply the history of techniques whereby men have sought to gain wives and mistresses; it is also the history of woman’s subordination to man. The ideals prevailing in any society, about courting, are those of societies dominated by men. All societies, at least since the rise of civilization, have created certain standards in the methods of obtaining wives, and women are expected to conform to those standards. Further, there have always been different techniques among different sections of society. Courting among the lower classes is always simpler and cheaper than among their superiors. Mr. Turner has made the latter point but does not give it the importance it deserves.

The book does contain a wealth of information; particularly effective are the sections dealing with romantic love in mediaeval Europe. As Mr. Turner has pointed out, the poetry, songs, fantastic dresses and gaudy battles between rival suitors in twelfth-century Europe were attempts by knights and nobles to render life in castle and manor house more interesting. An important factor here perhaps was the tedious length of a northern winter, with poor lighting and meals made dull by lack of fresh food; there was nothing for a man to do on a dull day except make love, sing songs or listen to the ardent troubadours. Although the courting of the 12th century appears to us to be filled with hypocrisy and vain, useless elaboration, human experience in what is a very important activity was permanently enriched.

The rise of modem society led to a further development of the ideals of romantic love. Courting, in mediaeval Europe the pastime of bored nobles seeking interesting experiences in seducing other men’s wives, became under Capitalism the most usual method of obtaining a wife. The idea of marrying for love is the product of a society that proclaims loudly the freedom of the individual. From this individuality there grew also the idea that women were the equals of men. socially and economically, though this freeing of woman from man’s domination is still not complete even in the limited context of Capitalist freedom.

In the 20th century the breakdown of the prudish moral standards of the 19th, together with the increasing conviction of the importance of sex, has led to new freedom in courting habits. Alongside this has gone some decline in courting. Courting has frequently been limited by economic factors; people are usually limited to their own class and even their particular group in their choice of mates.

At the present time the nature of our society is tending to disintegrate social life, and thereby people’s individual lives as well. Everyone watches his own TV, minds his own business, makes his own way in the world, drives his own car, has—or wants to have—his own little suburban castle. There is little getting-together: the modern slick pub and dance halls seem poor substitutes for the communal gatherings of earlier times. Parties today often degenerate into that most unsocial of activities, watching the television. Entertainment is secondhand, and much of modern courting technique seems secondhand, too. Courting is declining into something altogether more flippant, casual—and unrewarding.

Mr. Turner sheds light on these and many other points. It is a pity that he does not adopt a more serious approach; as it is, this book could perhaps best be described as a humorous anthology of facts, opinions and quotations. It hardly achieves the purpose professed in the introduction; “to trace the progress of courting in the western world from the day of the troubadour to the day of the crooner.” Perhaps, too, a little less quotation and a little more generalization would have made a more interesting book. Not to be ungrateful; Mr. Turner has provided a gold-mine of interesting and amusing stories.