Disability: Models of Meaning

Much has been made in the media in recent years about the growing costs associated with meeting the needs of elderly and disabled people under the current social system known as capitalism.

Much has been made in the media in recent years about the growing costs associated with meeting the needs of elderly and disabled people under the current social system known as capitalism.

Politicians are never shy when it comes to declaring that ‘we need to do something about the growing problem of an ageing and disabled population’

Disabled people, up until around the mid 1990s and the introduction of the Disability Discrimination Act (1995) tended to be the poor relation of various other minority groups when it came to legal protection and making it unlawful to discriminate against someone on the grounds of their perceived ‘identity’.

Up until the 1970s it was all too common for children born with disabilities to be either ‘given-up’ by their parents voluntarily, or worse still, have them forcibly removed by the authorities and placed into asylums for the ‘insane’ and given the title ‘mental defectives.’

Lennox Castle ‘Hospital’ in North Lanarkshire, Scotland, was one such place where many of those went on to spend a lifetime ‘employed’ in the workhouse doing menial jobs, or alternatively spending their days doing nothing.

Lennox Castle was typical of large institutions built by local authorities in the 1930s and was the largest in the UK. Built to accommodate around 1300 people, it frequently exceeded those numbers by many more hundreds. Lennox Castle has become well known as an example of a particular type of provision characterised by its isolation and by a certain notoriety among members of the public and nursing professionals.

Lennox Castle represented a ‘large investment’ by the Corporation of Glasgow at the time, which bought the land and built the hospital. However 60 years after it opened, it was closed down.

It has been documented that some of the patients (perhaps more accurately described as inmates) went on to form relationships from which babies were produced, only for these to spend the rest of their lives within the walls of Lennox Castle too. Thankfully the social stigma and misunderstandings that surrounded people with disabilities at that moment in time is now pretty much a thing of that distant past.

Legislation

Prior to the DDA (1995), there was in place legislation that outlawed – for example – employers discriminating against someone on the grounds of their sex (Sex Discrimination Act 1975) and also the Race Relations Act of 1976,which made it unlawful to discriminate against someone on grounds of the colour of their skin, nationality or ethnic origin. Of course, that’s not to say it stopped it from happening altogether.

In more recent times, any kind of discrimination against these minority groups have been outlawed together under the umbrella of The Equality Act (2010) and to facilitate same sex marriage, The Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013.

All well and good you might think.

But are we really any closer to achieving anything like true equality under this grossly and inherently unequal social system known as capitalism?

As someone who is Registered Blind and depends on a Guide Dog to help me get around, this subject is of particular interest to me.

Medical Model v Social Model of Disability

Many people – mainly those who might find themselves in otherwise ‘good health’ – might be inclined to err towards the medical model of disability thesis. In broad terms this effectively says that people are disabled because of their impairments (legally defined as the limitation of a person’s physical, mental or sensory function on a long-term basis) or differences.

Under the medical model, these impairments or differences should be somehow changed by medical interventions and other treatments, even when the impairment or difference does not cause pain or illness. The medical model looks at what is ‘wrong’ with the person and not what the person needs. It creates low expectations and leads to people losing independence, choice and control in their own lives.

The social model of disability, on the other hand, says that disability is caused by the way society is organised. In particular the built environment, rather than by a person’s impairment or ‘difference’. It looks at ways of removing barriers that restrict life choices for disabled people. When barriers are removed, disabled people can be independent and relatively equal in society, with some choice and control over their own lives.

Disabled people developed the social model of disability because the traditional medical model did not explain their personal experience of disability or help to develop more inclusive ways of living. Some examples might include a wheelchair user wants to get into a building with a step at the entrance. Within a social model solution, a ramp would be added to the entrance so that the wheelchair user is free to go into the building immediately. Under the medical model, there are very few solutions to help wheelchair users to climb stairs, which all too often excludes them from many essential and leisure activities.

A teenager with a learning difficulty wants to work towards living independently in their own home but needs help with cooking, cleaning and quite probably money matters. Within the social model, the person would be supported by a carer (formal or informal) so that they are enabled to pay bills and live in their own home in the community. Under the medical model, the young person would be expected to live in a hospital or institution – most probably because it would have been the cheapest option.

A child with a visual impairment wants to read the latest best-selling book to chat about with their sighted friends. Under the medical model there are very few solutions, but a social model solution ensures full text audio-recordings are available when the book is first published. This means children with visual impairments can join in with such activities on an equal basis with everyone else.

Conflicting legislation

Of course, barriers are not just physical. Attitudes found in present day society, based on prejudice or stereotype, also disable people from having equal opportunities to be part of society.

I personally and frequently encounter access refusals when accompanied by my guide dog to private hire taxis, as well as in both Indian and Chinese restaurants, where culturally dogs are deemed to be ‘unclean’ and their saliva ‘toxic’, particularly within the Muslim faith. It is believed that should a Muslim person come into contact with dog saliva, it will ‘void them of their state of purity.’

This can be a particularly challenging situation when two competing pieces of legislation collide and compromise is hard to reach.

There was a difficult case that ended up in the courts several years ago, whereby a young Muslim man lost his sight and had to depend on a guide dog to help him get around. Not only did it take much persuasion for his parents to agree and allow their son to have the guide dog in the first instance; that it seemed was only the beginning of his problems. Unfortunately, the Iman of his local mosque refused him access on religious grounds. There was a stand-off and eventually the case had to be heard and decided by a judge, who eventually ruled that Disability Laws should trump Religious Beliefs and Laws, and so it was found that the boy had been discriminated against and must be allowed entry to the mosque along with his guide dog, as well as receiving substantial compensation.

Employment problems

It would be wrong to suggest that the rights and quality of life of the disabled have not improved considerably compared to the dark days of an institutional existence, with some now living relatively independent lives in supported accommodation.

But is there scope for all of our lives to be improved further? As a socialist and proud member of the disabled working class, the plain and simple answer is yes.

It is common knowledge that there exists a high proportion of disabled people both in the UK and elsewhere in the world who are denied fulfilling work opportunities because they are deemed to be a high liability by potential employers and likely to cost more in terms of days off and lost production and consequently lost profits, should their situation worsen.

For those who develop conditions while in employment, days off for treatment are frowned upon, and any production time lost invariably has to be ‘made-up’ by the employee in their ‘own time’. There are very few employers out there who take a sympathetic view of a worker’s health condition if it has a detrimental impact upon their profit margins. And more often than not, a ruthless capitalist will think nothing of ditching an unproductive worker.

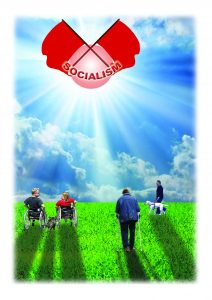

Within a socialist society, on the other hand, where people will be the priority as there is no pursuit of profits, there will be no need to fear losing one’s job and subsequent income, because wage earning and the selling of one’s labour in order to survive will be destined to the annals of history, along with the irrational and insane relationship between the buying and selling of goods and services to one another.

Instead, we the working class will take control over our own destiny, with each and every one of us living a full and dignified life in accordance with our own unselfish needs, contributing to the welfare and common good of the whole of our communities in accordance with our own unique and individual abilities and skills.

Those who are fit, able and desire to work, will avail themselves of the tools necessary and free in order to enable them to do so. Those who cannot, can be assured of a decent quality of life without the insecurity of having to depend on government handouts that barely cover what is needed in order to sustain basic human needs and life itself.

PAUL EDWARDS