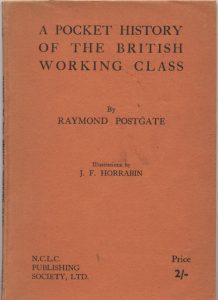

Pocket History of the British Working Class

One of the faults of Postgate’s “Pocket History of the British Working Class” (N.C.L.C., 2s.) is that it is far too short to deal with the tremendous amount of material. The effort to compress working class history into 90 pages must result in the omission of much that is important. This, however, is not our only criticism, as while the book serves well as an introduction to the study of the infancy of the movement, the latter part, from the formation of the Labour organisations onwards, contains some inaccuracies.

One of the faults of Postgate’s “Pocket History of the British Working Class” (N.C.L.C., 2s.) is that it is far too short to deal with the tremendous amount of material. The effort to compress working class history into 90 pages must result in the omission of much that is important. This, however, is not our only criticism, as while the book serves well as an introduction to the study of the infancy of the movement, the latter part, from the formation of the Labour organisations onwards, contains some inaccuracies.

The difference between the craft guilds of the journeymen and the Trade Unions is shown quite well. And a good outline is given of the efforts of the unions and sympathisers to gain a legal standing for the unions by the repeal of the Combination laws.

The Owenite movement is touched upon, but none of the other Utopians, such as Richard Hall, A. Combe, and John Bray are mentioned. The writings of these men played an important part in the theoretical side of the workers’ movement in the early nineteenth century and a knowledge of their ideas is very useful to any student of working-class history.

The Chartist movement is summarised fairly adequately; the course of the movement, the disputes over the questions of violence, moral force and compromise, and the waning of enthusiasm, which eventually led to its break-up, are very well described. The wild statement of Stephens, given on page 30, “limb for limb . . . blood for blood,” could have been followed by this statement of Lovett, a striking contrast: “All this hurry and haste, this bluster and menace of armed opposition can only lead to premature outbreaks and to the destruction of Chartism.’ (History of British Socialism, Vol. 2, page 43, M. Beer.) One lesson we have learned is that the working class cannot maintain and sustain its movement by using violence against their employers or the State.

With the collapse of the Chartist movement and the rise of the “new model” unions, the workers seek concessions on the industrial field, and we have a short period of stagnation politically. We see large amalgamated unions arise which attempted to work in a spirit of co-operation and conciliation with the employers. Despite their activities, strikes occurred in many industries and widespread discontent existed. The Reform Act of 1867, giving the vote to town workers, and certain other concessions obtained, led the members of these unions to support the Liberals in elections, and some of their leaders went into Parliament as Liberals. In fact, as Postgate says on page 56, “Politically they become indistinguishable from party Liberals.”

We now come to what must be considered the less satisfactory part of the book. When reading a work dealing with Socialism and Socialists, a newcomer would at least expect a little enlightenment as to what Socialism means, and an indication of how to establish it. In this work he will look in vain. Postgate classes all Labour organisations, with the exception of the Labour Party at its foundation, as Socialist, but differing in their methods of obtaining it. “Class war, the dialectic, no compromise, no reforms—the revolution or nothing. These were S.D.F. principles.” (Page 68.) This is far too sweeping a statement, as the S.D.F. throughout their history were advocates of reforms.

We are. told that the work of Keir Hardie and the I.L.P. was “the making of Socialism a mass movement instead of a clique’s doctrine ” (page 64). Yet forty-seven years after they were founded, C. A. Smith, their chairman, wrote in the New Leader, March 14th, 1940, when referring – to Socialism: “Clearly it is high time for Socialists to get down to the job-of definition, and make quite clear to themselves what they mean by the term.”

Although Postgate refers to the Labour Party as Lib.-Lab„ he infers, generally, that they were Socialist—e.g., page 66: “The propaganda of Socialism had at last reached the masses.” This is stated because 29 Labour men had been elected to Parliament. Non-Socialist organisations such as the Fabians, the B.S.P. and the Labour Party are paraded through these pages, but the silence regarding the S.P.G.B. is complete.

Again, when dealing with the first world war, he omits any reference to the consistent Socialist attitude of the S.P.G.B.—an attitude based on understanding—yet he mentions the opposition of the I.L.P.

It is suggested that the two Labour Governments were prevented from passing Socialist measures because of the possible opposition from the Liberals (page 78): “A full Socialist programme was ruled out by the Liberal veto.” The truth is that the Labour Party, being a non-Socialist organisation, could do nothing other than administer capitalism, with all its defects.

In general, therefore, this is a useful work so far as the early history of the movement is concerned, but in the latter sections the reader should proceed warily and critically.