BookReview: The Oppressed Sex

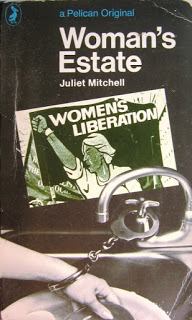

Woman’s Estate, by Juliet Mitchell. Penguin Books 25p.

Woman’s Estate is an absorbing and by turns, irritating and perceptive analysis of the nature of women’s oppression, and the rise and contemporary position of Women’s Lib.

of the nature of women’s oppression, and the rise and contemporary position of Women’s Lib.

The kernel of Mitchell’s book is the comparison she makes between the two implicit wings of the Women’s Lib Movement, which she labels “Radical Feminist” and “Abstract Socialist”. The polemic is well argued and substantially documented and concludes with an effective rejection of the intellectual position of the “radical feminist”:

To say that sex dualism was the first oppression and that it underlies all oppression may be true, but it is a general, non-specific truth, it is simplistic materialism, no more . . . There have always been classes, as there have always been sexes, but how do these operate within any given specific society? Without such knowledge (historical materialism) we have not the means of overcoming them. Nothing but this knowledge and the revolutionary action based upon it, determines the fate of technology — towards freedom or towards 1984.

But Mitchell also partially rejects “classical socialist theory” because of its “inadequacies”. The conceived “inadequacies” are two-fold. “The position of women in the work of Marx and Engels remains dissociated from, or subsidiary to, a discussion of the family, which is in its turn subordinated as merely a pre-condition of private property.” Yet no substantive reasons are given as to why this view is inadequate. We are told that “the framework of discussion fails noticeably to project a convincing image of the future, beyond asserting that socialism will involve the liberation of women as one of its ‘constituent movements’.” In this connection Engels’ projection that the emancipation of women becomes possible only when women are enabled to take part in production on a large, social scale, is implicitly rejected. Later, however, it is argued that although 42 per cent of the United States labour force are women, the exclusion of these women from the work-force “at the most formative period of their lives from the point of view of the development of class-consciousness” accounts for the lack of political insight shown by women.

The resolution of this paradox requires that we take note of Mitchell’s second major perceived inadequacy associated with “classical socialist theory”, in that it ignores the findings of psychoanalysis: “To ignore Freud is like ignoring Marx.” Thus women’s lack of awareness is intimately associated with her function in the family, which in turn is “the source of the psychic creation of individuals.”

In order that we might be prepared to accept the relevance of Freud to an understanding of how women become women, Mitchell turns science on its head. The empirical validation of hypotheses is unnecessary—evidence is seemingly secondary to unsubstantiated intuition. Yet even accepting that Freud’s insights have apparent explanatory (if not scientific) power in that they suggest how a woman “comes into being”, their power is related specifically to the social situation of mankind. As Mitchell herself implies, the “bio-sexual interpretation of the anatomical-biological” is made in a social context. Freud’s ideas may account for contemporary notions as to the nature of “woman”, but these notions are related to social situations through time and space; they do not tell us what “woman” is but only what a particular woman thinks she is, or is thought to be. It is as though the argument went that to understand the behaviour of a footballer relative to a member of the opposing side, reference should be made to the nature of the opponent rather than to the game as a whole, and the context in which it is played.

To suggest that “classical socialist theory” fails to project a convincing image of the future is to require that it formulates solutions to a problem which it considers largely irrelevant. It is not the specific nature of the image which is important or the particular manifestation of oppression. What is central is the idea that the image and the oppression are characteristic of a class society: the former will be redefined, the latter eliminated, in a classless society.

Nevertheless this book deserves attention. There are some interesting comparisons with other protest movements —black power, students, hippies, etc.,— and the book is packed with specific examples of contemporary discrimination directed against women, and with rewarding clues as to its essential precondition. In documenting the pervasive power of oppression at every level the author has remedied an obvious informational deficiency.

M. D. G.