Book Review: The Trial of Charles de Gaulle

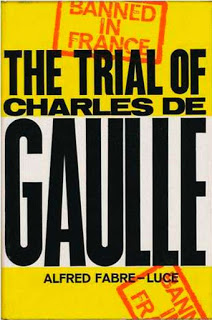

The Trial of Charles de Gaulle. by Alfred Fabre-Luce, Methuen, 30s.

Only English readers well up in French politics are likely to face this book on equal terms. And we doubt whether all that number of French readers would have coped so easily either, had they been able to read it; which they were not, by the way, since it was banned in France.

Only English readers well up in French politics are likely to face this book on equal terms. And we doubt whether all that number of French readers would have coped so easily either, had they been able to read it; which they were not, by the way, since it was banned in France.

The trouble comes from unfamiliarity with most of the personalities, and the complexity of the events; all capitalist politics are unsolved, we know, but French politics must be the most involved of the lot. The machinations, the intrigues, the conflicts of interest, the complex struggles for power, are really intimidating to the outsider.

Things are not helped by the author’s device of a mock trial for the General; the result of this is to allow free scope to the much greater latitude in French courts for fact to be mixed with fiction, and to make it all the harder to sift the real from the opinion and the hearsay.

The idea of political trials does not come too startlingly in France, where they have a long history going back to before the Revolution. We are reminded in the introduction, in fact, that it is not so long ago that a hundred members of the Vichy government were put on public trial, including the former head of state, Pétain. Some of the accused, like Laval, actually ended up before a firing squad. In contrast, the last such trial in England goes back to 1805.

From what we are able to gather, however, Mr. Fabre-Luce himself seems really to be opposed to the idea of political trials and only uses the mock-up of one against de Gaulle to bring the General and his activities into the arena of public debate. In particular, the only punishment postulated for the accused, should he be found guilty, is a vote of censure.

The author extends the device further by allowing de Gaulle to remain silent during his trial, using as actual precedents Pétain and Salan, who also kept silent at theirs. This gives him full scope to marshal the arguments for and against the accused, mostly in the form of real statements by real persons, though he also brings in a few fictional characters; even these, however are used as convenient mouthpieces for real statements representing other general and well-known points of view. The whole thing is done very cleverly, the atmosphere of the trial being particularly well captured.

As for the arguments, suffice it to say that telling points are made, and others seem to be made, by both sides. But, perhaps because one is a very much detached observer, the only feeling at the end is of indifference and unreality. Both accusers and defenders seem obsessed with a personality—de Gaulle. For some, he is the personification of all that is noble, all that is right, all that is good; for the others he is the embodiment of evil, Satan incarnate. For his defenders, he represents salvation; for his accusers, he is the agent of damnation. Leader or devil? Military genius or upstart colonel? Far-seeing prophet or arch-traitor? Liberator or renegade?—these are the terms in which the debate is conducted. It is altogether too superficial and unconvincing.

The result may be witty and entertaining, but it does not get us very far. All the fine words and stirring speeches, the scintillating arguments and witty exchanges, fail to make us forget the harsh realities of French life during the past thirty years—the misery of a second world war in twenty years, the hardships and terms of the occupation, the agony of Indo-China, the criminal folly of Suez, the bitterness and bloodshed of Algeria. Clever fantasies of word battles mock-fought over the alleged motives, virtues, and failings of one man have no relevance to problems such as these.

As a polemical exercise, the book can be given full marks. But for what it tells us of importance concerning the political and economical realities facing French capitalism and—much more important—the French working class, it impresses not at all.

Stan Hampson