Book Review: Divided Ireland

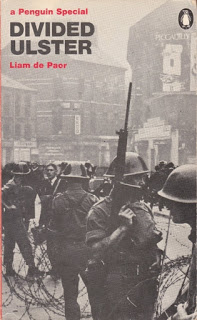

Divided Ulster, by Liam de Paor (Penguin Special. 5s.)

Divided Ulster, by Liam de Paor (Penguin Special. 5s.)

“In Northern Ireland Catholics are Blacks who happen to have white skins”. Liam de Paor’s analogy has some validity when Catholics in their areas of Derry and Belfast are compared with Negroes in their ghettoes in some American states. Northern Ireland, the more capitalistically advanced geographical area of Ireland, has even in this advanced phase of capitalism a working class who are led to believe that religion divides them, and this division causes sufficient hate for sectarian conflict. The historic division into Catholic Ireland and Protestant Ireland has been much more intense in the remaining six-county British “colony” because Protestants form a two-thirds majority whereas in the other counties their numbers are negligible.

Threats to English rule in the 16th and 17th centuries were mostly instigated by the Celtic dynasties of the Northern part of Ireland — of which the O’Neills were most prominent. Confiscation of land by the natives from Cromwellian Protestant settlers intensified suspicions between the two groups. In this way “the complex struggle for power and property in Ireland, as the civil war was in England. manifested itself as a religious war”. Ulster was used as a base for the Williamite conquest which was settled finally by the defeat of the Catholic James II at the river Boyne in July 1690 and enthroned the never-to-be-broken Protestant succession to the British monarchy. The aftermath of “the Battle of the Boyne” saw the consolidation of Protestant rule by anti-Catholic laws “designed essentially . . . not to convert them to any form of Protestantism, but to prevent them from obtaining as a group, property, position, influence or power”.

The tribal system of Gaelic Ireland was not broken until after English rule was established there. Feudal Ireland matured under English rule. The Catholic natives mostly worked the land and the Protestant landlords found this quite profitable because the Catholics paid high rents. In Ulster competition for tenancies was so keen that Protestants were forced to combine in groups whose purpose was to attack and maim Catholics. Catholics also found it necessary to combine for similar reasons.

Industrial advance in Belfast and Derry produced a working class among Protestants and Catholics alike. Poorer peasants sought work in industry and drifted towards Belfast and Derry from other parts of Ireland. Competition for jobs became keener and Catholics were often prepared to work for less than their Protestant counterparts. The Protestant majority overcame this by combining under a religious cloak against the Catholics.

Catholic influence, ownership and power was generally on the increase in the island as a whole. Catholics Emancipation campaigns ended the penal code, and thus enterprise among Catholics was increased with a consequent increase in their power.

In the North Eastern part of the island, the capitalists and landlords capitalised on the resentment which Protestant workers felt towards Catholic workers. Through discriminating against Catholics in an area with large numbers of Catholics and Protestant workers, religion became a cloak for real economic reasons. The more Home Rule came near to becoming a reality, the more Catholics and Protestants were divided by their exploiters. The capitalists in Northern Ireland quite rightly knew their interests lay in British rule and believed that Home Rule would mean being reduced to the agricultural and economic backwater which the rest of Ireland was. But this “divide” policy could only work where there was a Protestant majority.

Resistance against Home Rule on a large political scale and a raging guerrilla war for Independence resulted in a compromise— a parliament representing 26 counties in Dublin and one representing six counties in Belfast. The Belfast parliament was soon discovered to be an effective means of maintaining the British economic connection against republicans, but with the advantage that more effective legislation relating to Northern Ireland’s capitalists’ political problem could be invoked against any threat to sever this connection.

The economic advance of the South in the 1960s and the decline of the major traditional industries in Northern Ireland; the decline in emigration from the South and the decrease in between the standards of living between the two states would suggest that the economic reason for the existence of separate states was marginal.

However, the Craigs, Chichester-Clarks and all the other historical hangovers found that the Parliament forced upon them in 1921 became their life-saver in 1969 when their political existence was threatened by the civil rights movement which had successfully united Catholics and some Protestants. Along with the Civil Rights Association, the People’s Democracy marched, Protestant with Catholic, demanding rights to housing, employment and local election voting. Police and Protestant Orange assaults on the marchers finally erupted in near civil war. British troops were sent in. It appeared that the Orange Order was foundering together with its implement of power, the Belfast parliament. However, through the good services of the Free Presbyterian Church on the one hand and of the more moderate members of the Order on the other, Protestant [and] Catholic workers became increasingly divided and the influence of the CRA and PD declined almost completely.

The battle was now waged by Catholic workers against Protestant workers and intensified on both sides by opportunist extremists. De Paor aptly quotes Pearse:

When the Orangemen ‘line the last ditch’ they may make a very sorry show; but we shall make an even sorrier show, for we shall have to get Gordon Highlanders to line the ditch for us.

How oppressed the Bogsiders were was shown when they welcomed the British troops — oppressors in the disguise of protectors. But soon the troops were forced to oscillate between “protecting” one side from the other and using methods which, if used in South Africa, the British Press would have denounced as “fascist”.

Socialists recognise one evil, capitalism, whether or not the method used for its maintenance is political democracy. The struggle in Northern Ireland continues, but it is a struggle to maintain the present out-dated managers of capitalism against a newer capitalist class. The workers have nothing to gain from this fight; but once again they are allowing themselves to die for capitalist ideals.

All inspired but misguided republicans should heed what James Connolly said:

If you remove the English army tomorrow . . . England would still rule you . . . through the whole army of commercial and individualist institutions, she has planted in this country.

The sad part of these struggles is that so much effort on a world scale would end today’s problems — capitalism.

While Liam de Paor does not give a Marxist analysis of Northern Ireland he does nevertheless provide workers with a valuable introduction, to a case study of, the Northern Ireland problem.

Patrick Garvey