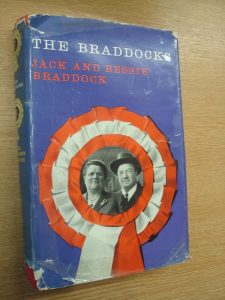

Book Review: ‘The Braddocks’

A Labour leader looks back

‘The Braddocks’, by Bessie Braddock, M.P., Macdonald, 30s.

When Labour achieved its landslide victory under Attlee in 1945, one of its leaders (Mr. Greenwood, father of the present “shadow cabinet” minister) made a speech to the jubilant crowd of M.P.s at Westminster saying what a fine varied lot they were: barristers, solicitors, doctors, business men—as well as trade union leaders and the sons of toil. We do not recall that he said anything about noticing any Socialist among them; but no doubt this might be because it was taken for granted that they were all Socialists.

When Labour achieved its landslide victory under Attlee in 1945, one of its leaders (Mr. Greenwood, father of the present “shadow cabinet” minister) made a speech to the jubilant crowd of M.P.s at Westminster saying what a fine varied lot they were: barristers, solicitors, doctors, business men—as well as trade union leaders and the sons of toil. We do not recall that he said anything about noticing any Socialist among them; but no doubt this might be because it was taken for granted that they were all Socialists.

One thing, however, that it would be difficult for anyone to dispute about these hundreds of Labourites rubbing their eyes in surprise at finding themselves in the House of Commons is that they were as humdrum and anonymous a crowd of non-Socialists as you could find anywhere, and few of them made much of an impression in their new and elevated surroundings. Possibly it is because of this dull background that Bessie Braddock stood out so conspicuously.

This book is her life-story, intertwined with that of her husband Jack (who collapsed and died just after the book came out), and it is of some value in the picture it gives of working-class life on Merseyside and particularly of Labour and Communist activities there in the decades after the ending of the first war-to-end-war in 1918. The background is typical—poverty, strikes, police brutality—and set against that the typical reactions of the less apathetic workers like the Braddocks, trade union agitation, activity in the Communist and/or labour parties, cycling Sundays, reading Blatchford’s Clarion and in general believing in fighting for as many reforms as possible, for as much of the “something now” as you could hope to get. They thought somehow that these things added up to Socialism and would change the face of society.

In the case of many of the Labour leaders who achieved a certain amount of eminence as a result of their political activities one tries in vain to resist the feeling that they were mainly interested less in the “something now” for the working class which they knew to be a futile chasing of your own tail than in “What’s in it for me?” With both of the Braddocks one gets a feeling of honest effort misapplied. It is difficult to see how anyone could imagine that the policies of the Labour Party could have the slightest effect on the position of the workers as members of a property-less class forced to take their chance on the labour market. It remains true that most workers in 1945 (and no doubt just as many today) could not see things in the way a Socialist does. And from the evidence of this book the Braddocks qualified fully for the role of blind leaders of the blind. But at least they seemed to do so with more sincerity and less of the tongue-in-cheek attitude than some of their kind. The chapter by Bessie entitled “Surgery” seems to prove that.

Like so many Labour M.P.’s she fondly imagines that her regular “surgery” at which she would hear the special problems and complaints of her constituents were a meaningful exercise in keeping the sea of capitalism’s problems from beating around working-class doors. No doubt she could help with free advice which could be of some use at times. But then this applies to “poor man’s lawyers” (or even to the surgeries run by Tory M.P.’s). To anyone prepared to look a little below the surface the very name “surgery” should have been a warning of futility. For how often does it happen that a doctor will use his skill and his science in trying to cure his patients, knowing that they leave his surgery to go back to the very conditions that causes the illnesses—poor food, bad housing, the worry and neurosis caused by keeping up with the rent or the mortgage or the latest speed-up at the factory. But the Braddocks of this world seem to close their eyes to the real truths of our way of life.

Two matters of special interest in this book are worth the reader’s notice. The first is to do with the fact that the Braddocks were at one time members of the Communist Party and leading members at that. Consequently they were in a good position to see how that party was used merely as a mouth-piece for Russian state-capitalism—with the communists, having got rid of the notions of patriotism which bedevil most workers, merely replacing them with what might well be the slogan “My Russia, right or wrong.” A particularly illuminating item tells that in one period in the twenties (when the pound was real money) the income of the C.P. from contributions was £7,500, while the amount of funds received direct from Russia in the same eighteen months as no less than £85,000, a truly staggering sum for those days.

The Socialist Party of Great Britain (amongst others) often said that the CP was not a party that was supported entirely by working class contributions and that there must clearly be a Russian piper playing the time; there never was any other feasible explanation as to how such a small party could possibly afford the tremendous expense of running the Daily Worker.

The other point concerns Bessie’s opinions about Bevan who, at least since his death, has become almost beatified even by his opponents in the Labour Party. She retells the story of the arrest and prosecution by the Labour Government of three dockers from Merseyside—for the crime of striking! Sir Hartley Shawcross was the Attorney-General who ordered the arrests and Mrs. Braddock alleges that Bevan engineered him into that action so as to discredit a rival candidate for the post of Foreign Secretary to the place of the ailing Ernie Bevin. Yet Bevan himself told Shawcross: “The strikers are on their knees; now is the time to strike them.” (P. 105).

Still, Bessie goes on being a Labour M.P. and by all appearances remains as blissfully unaware of the sheer ridiculousness of it all as the workers who vote for her. She remains a likeable character: if only she would think a little more deeply and then throw her weight into the scales on the side of Socialism.

Lawrence Weidberg