Exhibition Review: Annie Swynnerton – Painting Light and Hope

Painting was one of many cultural areas from which women were once all but prohibited. Training was difficult, and women were generally barred from classes with nude models, which were seen as an essential part of artistic education. A number of women who did succeed were born into artistic households, often the daughters of painters. Annie Swynnerton (1844–1933) was one of the few women who overcame these problems, and in 1922 she became the first female Associate Member of the Royal Academy, which had been founded in 1768. She attended the Manchester School of Art and in 1879 helped to found the Manchester Society of Women Painters. However, she has been relatively neglected and a fair number of her works are either lost or untraced. An exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery, on until 6 January, is the first major display of her work in almost a century.

Swynnerton was also politically active, and joined the Manchester Society of Women’s Suffrage. The subjects of her portraits include prominent supporters of women’s suffrage, such as Millicent Garrett Fawcett, and also Swynnerton’s friend and fellow-artist Susan Dacre, who is in turn represented by a portrait of Lydia Becker, who had set up this society, the first of its kind. An early portrait by Swynnerton is of William Gaskell (widower of novelist Elizabeth Gaskell), where his face and hands and a newspaper are highlighted against his black suit and a dark background.

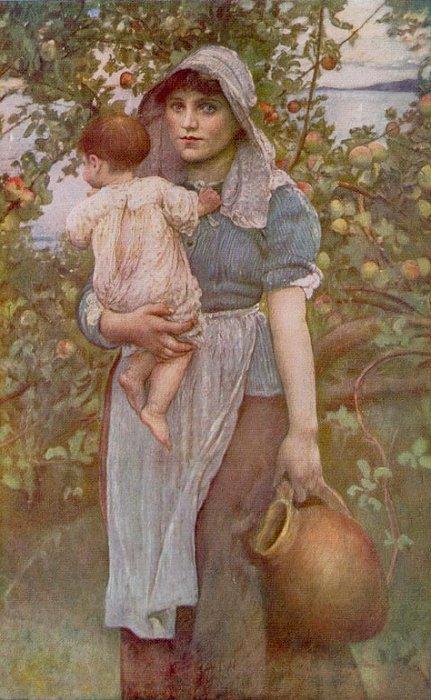

Swynnerton also painted many other depictions of women, from both Manchester and Italy, where she and her husband spent part of their time. Some of these were of poorer women, such as a young mother carrying her child while collecting water, and another of a convalescent. Her own nude studies can be quite powerful, as in one of Cupid and Psyche, which includes bodily features such as veins, so rejecting the conventional idealisation of the body. In Italy she also painted a number of landscapes and town scenes.

She was influenced by various artistic schools, including the Pre-Raphaelites and Impressionists, so her work can seem, as the accompanying catalogue notes, ‘perplexingly eclectic’. But the exhibition demonstrates both the merit of Swynnerton’s work and her role in increasing women’s presence in art.

PB