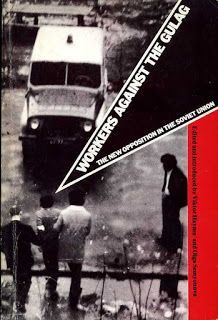

Book Review: Workers Against The Gulag

Workers Against The Gulag, edited by Olga Semyonova and Viktor Haynes. (Pluto Press 1.95)

Workers Against The Gulag, edited by Olga Semyonova and Viktor Haynes. (Pluto Press 1.95)

“I am a Russian worker, aged 46. I have worked in production for 30 years, 22 on electrical work, repairs. The archives of the KGB hold three folders of documents confirming that I am a skilled electrician, conscientious in my work, practically don’t drink, and don’t smoke.

“I will list some of the reasons which led me in 1959 to take the risk of illegally crossing the border, and in 1964 and 1966 to ask for permission to emigrate.

(1) The low level of pay . . . I have spent the best years of my life slaving for a crust.

(2) The lack of free Trade Unions.

(3) The cruel, humiliating treatment of men in Labour Camps. I spent many days in freezing solitary confinement in Camp No. 8 of the Omsk, UMZ.

(4) The continual ever-growing tendency of the KGB to use “psychiatry” to strengthen its punitive powers.”

On the 21 December 1976, V. A. Ivanov appeared in Revolution Square in Moscow with a placard: “To the Soviet Authorities. I demand permission to emigrate. I have gone through Hell in your Camps and Gas-Chambers. What else is left?” Ten minutes later Ivanov was seized, spent 24 hours in the police station, and was then sent home, out of Moscow. In November he addressed a letter to George Meaney, President of the American AFL/CIO: “I am a Russian worker, a highly qualified electrician with thirty years record . . . I ask you to help me leave Russia and thereby escape further persecution.”

This book is one of the most damning indictments to come from Russia so far, consisting of a series of documents smuggled out and published, for the first time, in Britain. These documents tell the facts behind the glossy government propaganda tracts. Ninety per cent of the Russian working-class are on piece-work rates, based on impossible so-called “norms”. The minimum official poverty line is 50 Roubles a week; 10,000 families in Leningrad alone fall below this line. Every Soviet citizen has to carry an “internal passport” (just like under the Czar), which is also a residential permit. In addition, every worker has to carry his Labour Book, giving his work record, and without which he cannot get employment. Food is dear, in winter often unobtainable, especially butter, milk and eggs. The average Russian citizen gets less than half as much meat as West European workers. Serious widespread strikes have broken out as in Novcherkass, and been brutally suppressed. These workers in their protests actually betray the same naiveté as their grandfathers did in 1905 when they appealed to the Czar (the Little Father); asking “Comrade Brezhnev to intervene on their behalf, and the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party to prevent the local Communist officials from persecuting them is as futile.

In their appeals they declare their support of the Russian system and say they want to “make it work”. The most moving, harrowing parts of the book are the accounts of the brutal persecution and ill-treatment of workers by the criminal thugs of the KGB and the Russian CP. For daring to protest against corruption (more rife in Russia than in New York), thieving of state property, swindling workers of their pay, rigging elections to the official state “unions”, workers have been dismissed, had their furniture and children thrown out on the street, in the depths of Russian winter, been beaten up in police stations, and sent to “Psychiatric Hospitals” and Labour Camps.

All of which shows how terrified the authorities really are. In spite of everything, with incredible courage, Vladimir Klebanov and his friends have formed a free Trade Union, demanded recognition, and appealed to the west for help, which the KGB with all its powers has failed to suppress. The first Russian Free Trade Union has been driven underground, but still exists. This book confirms our view of the anti-working class politics in Russia.