Mixed Media: ‘Marx in Soho’, & ‘Richard Hamilton at the Tate Modern’

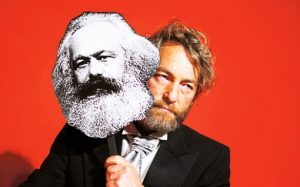

Marx in Soho

Marx in Soho, the 1995 one-man play by Howard Zinn was recently produced at the Marx Library in London directed by Sergio Amigo and starring Daniel Kelly as Marx. Zinn portrays ‘Marx as few people knew him, as a family man, struggling to support his wife and children’ in a ‘fantasy’ where Marx returns but due to a bureaucratic error not to Soho, London where he lived, but to Soho in New York City. Marx has returned ‘to clear my name!’

Marx in Soho, the 1995 one-man play by Howard Zinn was recently produced at the Marx Library in London directed by Sergio Amigo and starring Daniel Kelly as Marx. Zinn portrays ‘Marx as few people knew him, as a family man, struggling to support his wife and children’ in a ‘fantasy’ where Marx returns but due to a bureaucratic error not to Soho, London where he lived, but to Soho in New York City. Marx has returned ‘to clear my name!’

Zinn drew on insights into Marx’s private life in Yvonne Kapp’s biography of Eleanor Marx. Marx speaks of life in Soho: ‘we were living in London. Jenny and I and the little ones. Plus two dogs, three cats, and two birds. Barely living. A flat on Dean Street, near where they dumped the city’s sewage.’ Marx speaks about his favourite daughter Eleanor, ‘a precociously brilliant child’ nicknamed ‘Tussy’ who is ‘a revolutionary at the age of eight’, plays chess with ‘the Moor’ (the family nickname for Marx ‘because of my dark complexion’), drinks, smokes, and is enamoured of the Irish struggle which she learned from Lizzie Burns.

Marx is very witty: ‘Marx is dead! Well I am … and I am not. That’s dialectics for you’, ‘Understand one thing – I’m not a Marxist. I said that once to Pieper and he almost croaked’ and ‘My Ricardo! You pawned my Ricardo!’ Zinn invents a visit to his home by the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, no record of such a visit exists although they had met in Paris in 1844. Bakunin was an irrepressible revolutionary who arrived in London in 1861 at Alexander Herzen’s home, bursting into the drawing-room where the family was having supper. ‘What! Are you sitting down eating oysters! Well! Tell me the news. What is happening, and where?!’

Zinn portrays ‘Marx angry that his theories had been so distorted as to stand for Stalinist cruelties and to rescue Marx from those who now gloated over the triumph of capitalism.’ Zinn concludes the play with Marx proclaiming we should be ‘using the incredible wealth of the earth for human beings. Give people what they need: food, medicine, clean air, pure water, trees and grass, pleasant homes to live in, some hours of work, more hours of leisure. Don’t ask who deserves it. Every human being deserves it.’

Marx in Soho is highly recommended for socialist theatre-goers: ‘Look at it this way. It is the second coming. Christ couldn’t make it, so Marx came…’

************************************************************

Richard Hamilton at the Tate Modern

There was a major retrospective of the work of Richard Hamilton at the Tate Modern in 2014. He is acknowledged as the inventor of ‘Pop Art’ which he described as ‘popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business.’

There was a major retrospective of the work of Richard Hamilton at the Tate Modern in 2014. He is acknowledged as the inventor of ‘Pop Art’ which he described as ‘popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business.’

The exhibition reconstructs his installation Fun House, originally shown as part of the Whitechapel Gallery’s 1956 show This Is Tomorrow. It incorporates film, music, distorted architecture, op art and Hollywood film imagery and pin-ups such as Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Marilyn Monroe, and Robbie the Robot from Forbidden Planet. It is an homage to ‘Americana’, as well as a celebration of the new youth and ‘pop’ culture of 1950s capitalism.

In his 1956 collage Just What is it that Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? Hamilton has a muscle-man provocatively holding a lolly with the word POP and a woman with bare breasts wearing a lampshade hat, surrounded by emblems of the affluence of 1950s capitalism from a vacuum cleaner to a large canned ham. Capitalism is portrayed as ‘cool’, it was riding high in its ‘golden age’ of the post-war economic boom, the reformists believed capitalism could work in the interests of the working class, and Macmillan proclaimed ‘people have never had it so good.’ Hamilton particularly admired the German electrical company Braun and its Chief Design Officer Dieter Rams whose ‘consumer products came to occupy a place in my heart and consciousness that Mont Sainte-Victoire did in Cézannes’, and in 1964 he began to base works on Braun’s marketing images.

After the failure of Keynesian capitalism in the 1970s, Hamilton was horrified by the 1980s capitalist restructuring under Thatcher, and the reintroduction of unfettered free market capitalism. His 1984 installation Treatment Room is inspired by the bleak, clinical style of the capitalist state reflected in the DHSS office or NHS hospital waiting room. A TV monitor where the X-ray machine would be repeats footage of Thatcher from the 1983 Tory Party Conference. His War Games (1991-92) used TV news footage of the 1991 Gulf War which portrayed the war as a sport for viewers and reminds us of the BBC Newsnight coverage with Peter Snow’s sandpit and models. Later Hamilton portrays ‘war criminal’ Tony Blair as a gun-toting cowboy against a backdrop of military inferno in Shock and Awe (2010).

The Hamilton retrospective has some salutary lessons: you cannot ‘reform’ capitalism to work in the interests of the working class, and war is endemic to capitalism due to competition between capitalist groups for raw materials such as oil in the Middle East.

STEVE CLAYTON